Blogs

Why I Love Art: Greedy Eyes, Hungry Bengal

Tanvi Dhariwal

A nineteen-year-old in a studio. A mother desperate to save her child. An artist subverting a system.

Three years ago, I sat staring at a blank sheet of paper, trying to map my history in ink. My art professor’s prompt rang in my ears: show us who you are. Images of mangoes eaten under the scorching Delhi sun and summers spent under my grandmother’s coconut tree flashed in my mind. It was instinctive to view my childhood —my personal history — as my identity. Questions, however, began racing through my mind as I deliberated over the prompt. Was I merely the product of my lived experiences? Did those who came before me not shape me? Who was I if not a collage of my ancestor’s experiences? Is their joy, loss, anger and fear not coded into my very essence? I realised that I could not know myself without knowing those who came before me.

The history of my family, my community and my nation is one of conflict. It is a history of borders fraught with violence, unspoken trauma, homes lost and lives saved. My great-grandmother was in her early twenties when she left the tumult of pre-Partition Sindh with my grandmother in arms and husband by her side. They made their way to Bengal in search of a better life, unaware of the famine that had wreaked havoc on the population mere months before their arrival.

As I sat in the empty studio, many miles away from my ancestral homeland, I felt the profound absence of my great-grandmother; frustrated because I never had the opportunity to listen to her stories, to understand her experiences. My grandmother was too young to remember her journey from Karachi and her formative years in Bengal. Those who could remember were already gone. In an attempt to feel closer to my ancestors, I turned to the means I knew best – art archives. In the depths of texts and images, I found Chittaprosad: his inky pages, sharp lines and sharper ribs. Through a daze of melancholy and horror, I scrolled through page after page of prints and sketches as I, for the first time, visualised my family’s and community’s trauma.

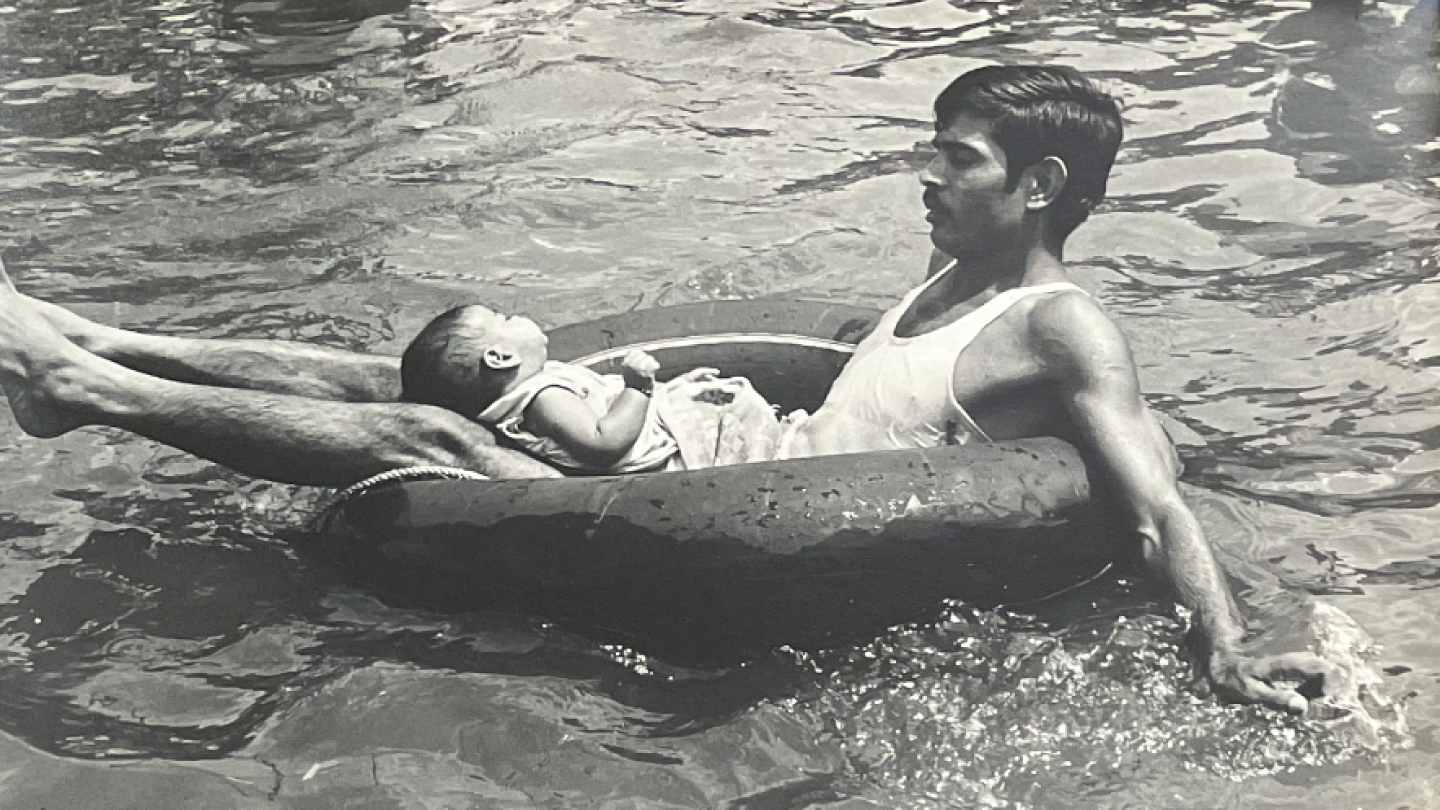

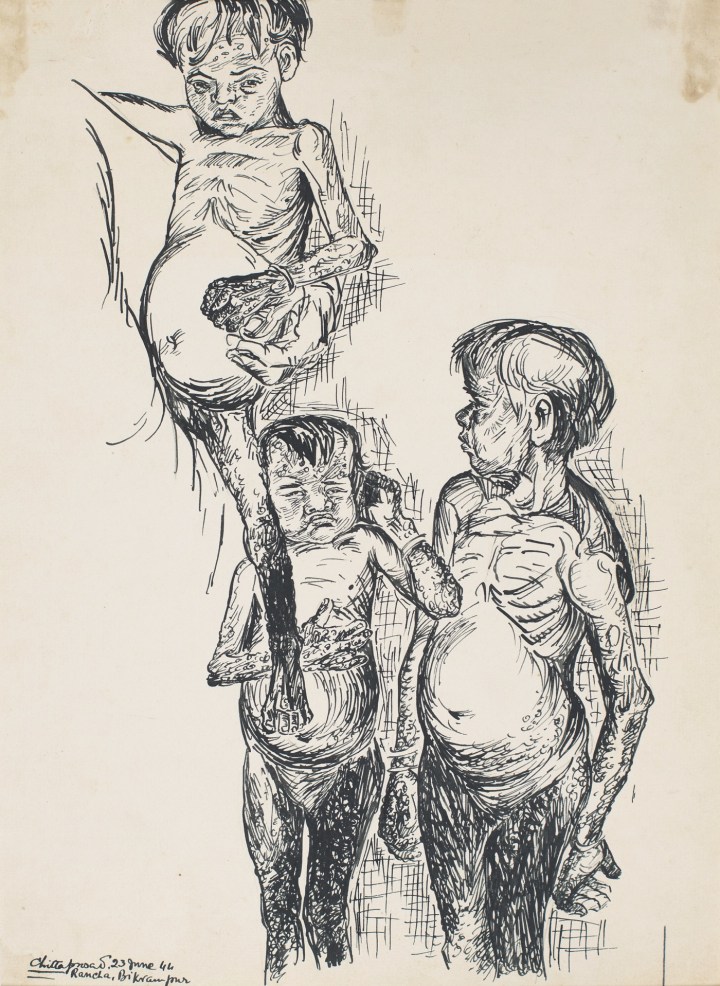

Children of Upendra Rishi Das, Rancha, Bikrampur, 1944, Ink on paper, Image courtesy of DAG

Chittaprosad’s publication Hungry Bengal is a collection of poignant sketches that document the Bengal Famine that killed an estimated twenty lakh individuals in 1943. Through depictions of starving children and weary adults, all characterised with protruding ribs and vacant gazes, he brought to life the harsh realities of Colonial India. It was this land of devastation my ancestors crossed over to with hope in their hearts. If this dismal reality of death and sorrow was their hope, then, I wonder, what were they leaving behind?

In my studio, I painted red and black lines. Small indistinguishable figures crowded the page as hours drifted by. Chittaprosad’s starved bodies were cemented in my brain as I attempted to create an abstraction of my family’s history. Suddenly, my family’s choices made sense – the root of their silent acceptance of hardship, their unwavering faith in an elusive higher power, their lack of desire to critique the cause of their circumstances and their intrinsic need to be good. The disjointed puzzle pieces that had once perplexed me now fit, their jagged edges hugged by broken corners.

Visualising the reality of the famine — of Partition and Colonialism — through Chittaprosad’s lens of defiance against oppression, helped me realise my family’s lens: the lens of the people who inhabited the sketches. They, unlike Chittaprosad, were not defiant. They did not wish to rise against capitalism or to subvert the authority of an oppressive system. They merely wished to survive.

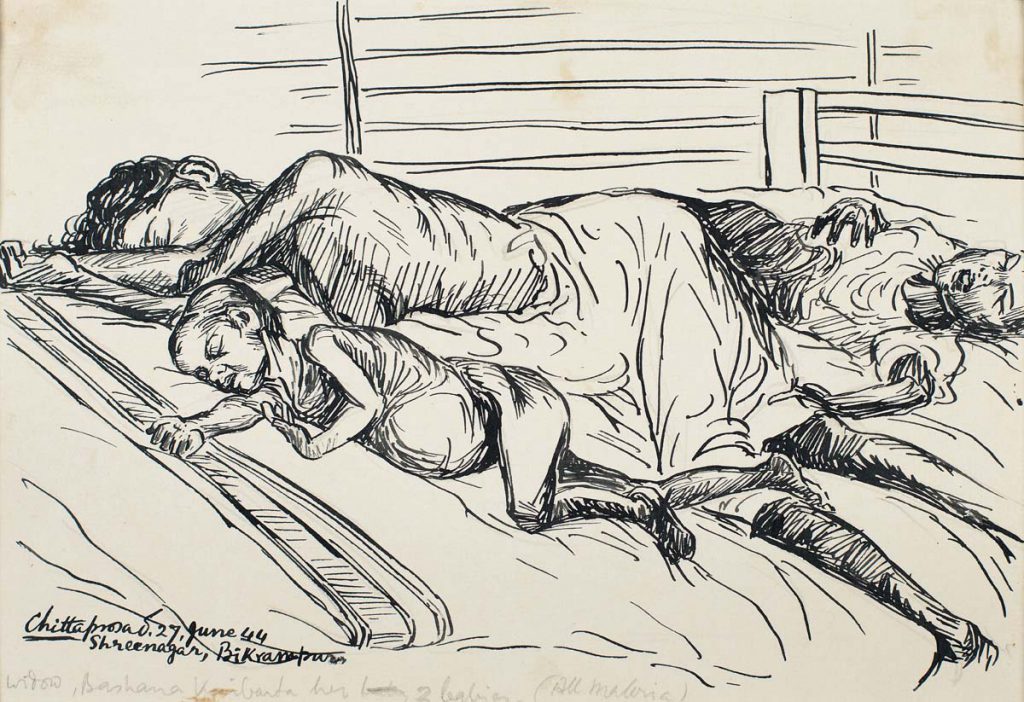

Bashana Kaibarta, E. R. Hospital, 1944, Brush, pen and ink on paper, Image courtesy of DAG

As I look at Chittaprosad’s Bashana Kaibarta, E. R. Hospital – 1944, I ask myself: would this woman, flanked by her sick children, have defied the system? Or would she, like my great-grandmother and a myriad of mothers across the subcontinent, simply have done what she needed to for her family to survive?

Tanvi Dhariwal is a recent graduate in Art History and Italian Literature, with an interest in the role of colonialism on material culture. Tanvi is also an artist and creates works that explore her family’s journey during the Partition.