Essays

Upon Passing, Mirroring, and Becoming

Stuti Bhavsar

A reflection on interface in MAP and AAAI’s latest exhibition, Bahurupee in the Panorama: Writing and Artwork of K.G. Subramanyan.

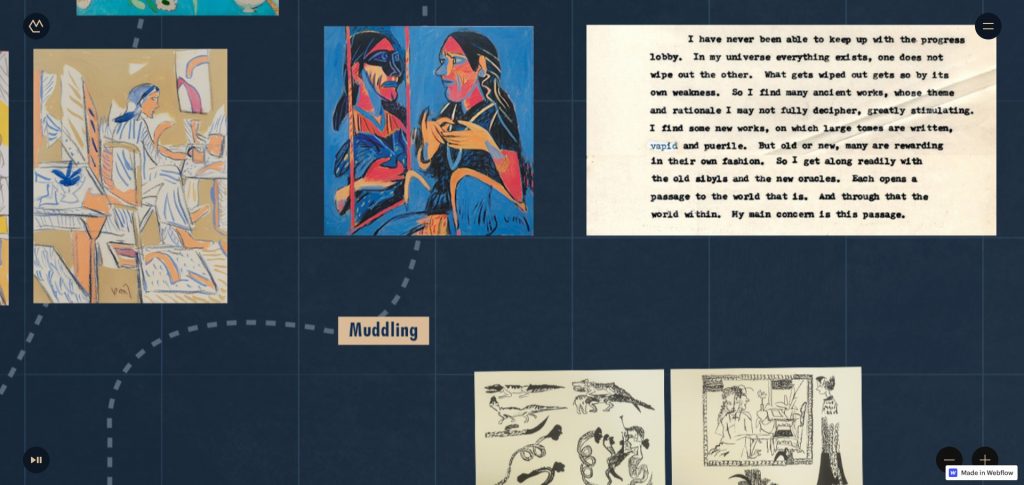

As a student, I observed K.G. Subramanyan activate interstitial spaces in various ways — terracotta reliefs animating the wall surface where forms fold and unfold; paintings weaving different moments of an event together as if reflected through mirrors; and murals, where the reliefs and paintings come together to endow building exteriors with a new life. These memories resurfaced while navigating the exhibition Bahurupee in the Panorama: Writing and Artwork of K.G. Subramanyan. Its web-based exhibition format mimics the Miro board — an online whiteboard tool that allowed its users and exhibition’s curators to brainstorm collectively, and create a mind map connecting diverse experiences akin to Subramanyan’s process.

When anonymous users work on the Miro board, the software attributes them names like Visiting Muralist, Writer, Explorer, and Sculptor amongst others — roles that I observed Subramanyan also play in his years of practice. Seeing the interface of the exhibition provoked me to look at the ways in which Subramanyan has employed the interface as a tool while urging the viewer to read between lines, materials and formats like essays, paintings, and reliefs. In the latter, an interface often provides a surface for the image, becoming a supportive framework. Instead, in this essay, I intend to foreground them as communicative devices that also give direction to a narrative by structuring episodes. Secondly, I attempt to see them in their physical and implied manifestations, stemming from my experience with the exhibition.

A screenshot of the exhibition Bahurupee in the Panorama: Writing and Artwork of K.G. Subramanyan, web-based, 2022

Passing

Branden Hookway defines the interface as “a shared boundary across which two or more separate components of a computer system exchange information. The exchange can be between software, computer hardware, peripheral devices, humans, and combinations of these.”¹

Image 1: Hide and Seek by K.G. Subramanyan, Charcoal and paper, 2008, Courtesy: K.G. Subramanyan Archive, Asia Art Archive

In the painting, one observes the character holding a flower pointing to something out of frame with its gaze fixed on a fish-like creature. Another arm below extends to reach for the fish as it moves towards the same direction as the pointed palm. Moreover, the arm on the right seems to rest on what is suggestive of a ledge. The shape of this arm mirrors the one above it (facing upwards) that doubly also appears like a tree trunk. Here, the interface — the implied edge between various spaces and interactions — gets marked by gestures, as the figure oscillates between the foreground and background, in turn becoming both.

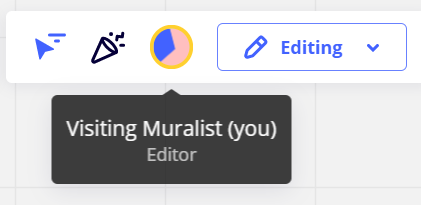

Image 2: Untitled by K.G. Subramanyan, Gouache on handmade gouache on paper, 2007, Courtesy: K.G. Subramanyan Archive, Asia Art Archive

Here, multiple exchanges at different spaces as seen from various perspectives are brought together. They are replete with reflections bouncing off each frame, from where the next sequence begins. Furthermore, in Hide and Seek, the virtuality of the interface is more in the mind’s eye with the seeker looking intently beyond the surfaces; in Untitled, virtuality is imaginary, with the interface being connoted by gestures; and in the exhibition, virtuality leans more towards the digital to generate possible readings through clues and connectors.

Owing to this, Subramanyan’s compositions can well be seen as kaleidoscopic panoramas, with characters interacting both in space and time. He playfully breaks the horizontality associated with sequences. This is equally activated by the show’s exhibition design — an aspect often seen secondary to the works in questions, and largely as an afterthought — that becomes central in this case. The exhibition is similar to Subramanyan’s murals, becoming an interface reflecting the environment around, tracing the shadows being cast — here, more as references. Even though the associations are worked out on an expansive scale, they draw the viewer back into the everyday life, in a more attentive way, instead of becoming a homogenised spectacle.

Mirroring

As a user faces the exhibition screen, their virtual palm meanders, drags, stops, enlarges, while encountering forms on the way, directing the gaze in multiple directions. An extension of the body, the cursor governs the user’s actions by subjecting it to certain conditions, making it a subject. At any instance, the users perceive only a section of the exhibition making one go back and forth. By disabling them from having a full view of the layout, the curators make the viewers occupy the position of Subramanyan’s characters travelling through different frames of images and references.

In doing so, the viewers embody the space of the board and tools like play, muddling, and discovery laid out by the curators to piece together resonances between Subramanyan’s processes. These readings and navigations add depth to an otherwise flat surface. The fragmented human experience remains at the core of Subramanyan’s works and the exhibition layout, be it when moving within/across the compositions, or at various distances when perceiving large-scale murals.

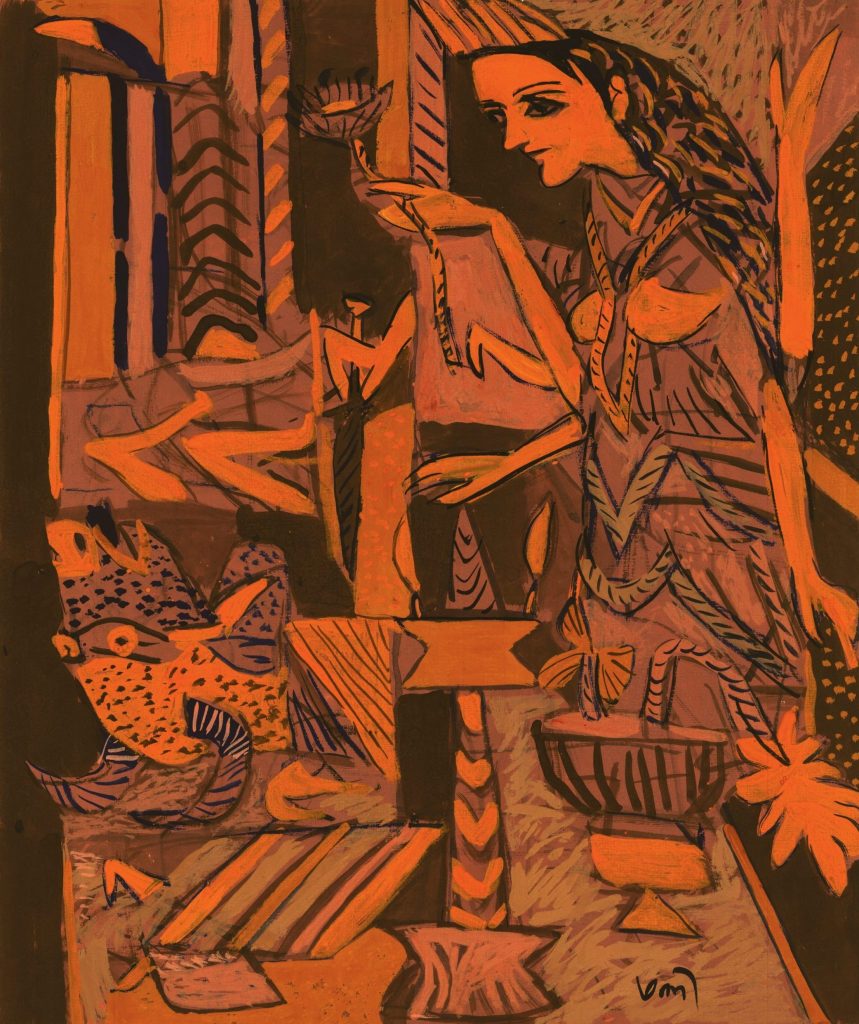

Image 3.1: The King of the Dark Chamber (Partial) by K.G. Subramanyan, Terracotta mural, 1963, Image courtesy: K.G. Subramanyan Archive, Asia Art Archive

Image 3.2: The King of the Dark Chamber (Partial) by K.G. Subramanyan, Terracotta mural, 1963, Image courtesy: K.G. Subramanyan Archive, Asia Art Archive

Becoming

Subramanyan’s murals are more than an ornamental appendage. They are meant to evoke reflections on the events and people associated with the building, and the values they espouse — be it the mural at Rabindralaya or at Mastermoshai Studio.³

In the former (The King of the Dark Chamber), the registers become stage-sets and characters turn mediators, guiding the viewers through various scenes and happenings. In image 3.1, the characters are see-through yet opaque, where they appear both as arches that become a part of their lower-halves and behind which they appear from.

Moreover, the patterns of the relief appear as mutating cellular units, considering the reclining character (on extreme left of image 3.1) that merges with the domestic space, becomes the courtyard-like frame and the serpentine form as it marks a shift to the next register. Here, the viewer, be it in front of the exhibition or the mural, is constantly travelling and reading through interfaces, and subsequently forging new relations with the environment. The body itself becomes an interface, transforming through space-time and personalities.

To conclude, repetition is crucial when Subramanyan improvises everyday forms and anecdotes, as they are baked into tiles, painted, mythologised, or analysed art-historically. Furthermore, to translate Subramanyan’s referential processes through an interface, the exhibition’s curators shifted focus from simply seeing to how observation actually operates. In turn, the interface as architectural reliefs, paintings and textual excerpts — that operate more as portraits of everyday life in the exhibition — all become passages4 that herald possibilities of being and foreground impulses of thinking.

A screenshot of the exhibition Bahurupee in the Panorama: Writing and Artwork of K.G. Subramanyan, web-based, 2022

All images of K.G. Subramanyan’s artworks in this essay have been used with due permission granted by Prof. R. Siva Kumar and are courtesy of Ms. Uma Padmanabhan.

Stuti Bhavsar is a visual practitioner, copy editor and researcher based in Bengaluru. One of her primary engagements has been to understand light as a vector in its various forms and intensities, vis-a-vis bodily sensorium, perception, and the interaction between a part and a whole. She currently works as the Programmes Coordinator for Reliable Copy, Bengaluru.

References

1. Hookway, B. (2014). “Chapter 1: The Subject of the Interface”. Interface. MIT Press. pp. 1–58.

2. Often in Mime, the separation between the actor(s) who plays various characters and the background is clear. In the painting, we see the figure becoming both background and foreground, and not necessarily play all the characters in the composition.

3. If we consider the flatness of images such as that on Mastermoshai Studio mural at Santiniketan, the foliage drawn on the surface appears like imprints of shadows cast by the trees around, which have been momentarily frozen. In an interview with Goutam Ghose, Subramanyan remarks about the same, saying how he would like the mural to act as a memory of the changing environment owing to urbanisation. His choice of using stoneware tiles and white slip mimicking cow dung is also reflective of practices he saw in and around Santiniketan.

Similarly, the Rabindralaya mural is based on Rabindranath Tagore’s play King of the Dark Chamber, cladding the first wall built when the cultural centre was being constructed in Lucknow. Instead of the surrounding space, the mural stands for the values of enlightenment and inner transformation — a value espoused by both the centre and the play. It is owing to this that the figures keep travelling through indoor and outdoor spaces (made more apparent by spacing where the surface of the base helps provide a breather for clusters of units with varying density) accentuated by shadows cast by the reliefs, as they venture towards light and experience enlightenment.

Ghose, G. (2014). “Magic of Making “K. G. Subramanyan””. Great Masters Series. YouTube.

4. Subramanyan, K.G. (1994). “Bahurupee: A Polymorphic Vision”. K.G. Subramanyan Archive. Asia Art Archive.