Essays

Understanding Adivasi Artists in the Contemporary Context

Mustafa Khanbhai

Giving viewers a sense of the context in which Bhuri Bai’s career has taken shape, this essay discusses how the art market and cultural institutions have historically engaged with indigenous art in India and the rest of the world. Conversely, it also examines the challenges faced by contemporary indigenous artists due to their unique position in an art world which valorises individual talent, while also exoticising traditional practices.

Indigenous art has been poorly contextualised and often misunderstood in the Indian and global mainstream for much of recent history. While impediments to public understanding of indigenous art began with colonial rule in the eighteenth century, they have continued and evolved into present-day forms as well. This essay seeks to inform the contemporary viewer of questions they need to consider when looking at the work of indigenous artists today, namely, the effects of the Indian colonial hangover and the position of contemporary indigenous artists caught between differing ideas of tradition and individuality.

Terms and categories like ‘Scheduled Castes’ and ‘Scheduled Tribes’ have been coined in the Indian Constitution to confer special rights upon certain marginalised or vulnerable communities in the country. The Indian Penal Code, which has historically been crafted to be flexible and minutely tailored to the varied communities to which it is applied, has invoked these terms in this spirit. This essay will avoid certain terms to describe indigenous groups, such as “primitive” and “tribe” or “tribal”. While from a purely linguistic perspective, the term “tribe” is a fairly innocent term, its application to indigenous communities comes with the implication of such groups being rudimentary and regressive social units.

When discussing indigenous or folk art in India, the term adivasi is perhaps most representative as it reflects a key concept in the discourse around indigenous societies, namely, the nuanced distinction between the original inhabitants of a land (from the Sanskrit adi, meaning ancient times, and vasi meaning inhabitants) and the settlers. The term dates back to events at Chotanagpur in the 1930s, when political activists demanded the creation of the new state of Jharkhand, but in more recent years, the word has sometimes been used pejoratively. This idea of indigeneity does not necessarily have to take the literal meaning that applies to “New World” countries but can also be used in the Indian context to forefront an alternative understanding of history and time. In particular, this latter sense of the term focuses on the adaptive, ever-contemporary nature of indigenous life and identity. It suggests a way of life external to mainstream concepts of historic progression and distinct from the urban classes founded on feudal and industrialist principles of organisation. Time is fundamental to this difference: the history of indigenous societies is one of slow, circular evolutions centred around a balanced relationship with the natural world and urban human settlements. On the other hand, urban settlements are the result of societies that have moved irreversibly through history, often undergoing dramatic changes at the cost of larger environmental and cultural systems to which they are subject. Finally, the essay will make frequent reference to the general art market, using terms like “mainstream” or “commercial” art, since nearly all the art in these markets is produced, financed and managed by non-indigenous people in urban areas.

Since the colonisation of India, and particularly since industrialisation, adivasi communities have had a difficult relationship with industrialised urban Indian society. Apart from the socio-political tensions between indigenous people and the expansionist projects of nation-building, the art produced by these communities has long been viewed with condescension or seen as “exotic” by mainstream art enthusiasts, often despite good intentions. Bearing in mind the subordinate position ascribed to indigenous art compared to mainstream Western or West-influenced art — or what is known as “fine art” — this essay will make little distinction between art and what is thought of as “craft” when discussing indigenous art practitioners. Although the essay will draw global parallels wherever relevant, the focus will largely remain on indigenous art in the Indian context.

The colonial impact on indigenous art and its lasting effects

Queen Mother Pendant Mask, 16th century, Ivory, iron, copper. Image courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In regions with significant indigenous populations, such as Australia and sub-Saharan Africa, colonial powers have fetishised and appropriated narratives around indigenous art and culture, especially since the nineteenth century. Art objects made in the context of indigenous, non-urban cultures that caught the interest of colonial officers in various parts of the world — for instance, brass statues from Benin or ritual masks from other parts of Africa — were taken as curios to become part of collections in the West. At best, this fascination can be seen as a testament to how alien one form of society may seem to another and at worst, a means to vilify indigenous cultures. As a result of the vast differences between the original indigenous context and the European societies in which these artefacts were studied, they were frequently misunderstood and misrepresented to the public.

Curio dealers such as Tost and Rohu Taxidermists, Tanners, Furriers and Island Curio Dealers, now known as the Tyrells Museum in Sydney, operated as middlemen who obtained indigenous artefacts and sold them to private collectors and institutions. These objects, originally possessing ritual or utilitarian value in aboriginal culture, became trinkets and ornaments.

Jivaroan shrunken heads at Ye Olde Curiosity Shop in Seattle, Washington, Late 19th – early 20th century, Digital photograph. Credit: Photograph by Joe Mabel

In the Americas, shrunken heads made by the Jivaroan people of the Amazon rainforest were commodified and imitated for the revenue they brought to curio shops in the US and Britain, altering cultural practices and belief systems by making Jivaroan headhunters a part of a global supply chain for the newly aestheticised objects. This also gave rise to incorrect conclusions about a community’s cultural values as seen through the lens of Victorian morality, which in turn bolstered, unsurprisingly, the frequent claim that colonisation was a necessary civilising mission.

Prior to colonisation in the Indian subcontinent, and particularly in the medieval period, Brahmin appropriation of adivasi deities and customs was used as a tool by which entire cultures were brought into the fold of Hinduism. A major example of this is the god Jagannath, who, according to scholars, was worshipped as Kittung by the Saora people of Odisha. Around the twelfth century, the kingdom’s increasingly influential Brahmin priesthood declared Kittung to be an avatar of Vishnu. Like other important Hindu deities, Vishnu was said to have many forms, each of which became part of Hindu — more specifically, Vedic or Brahmin — mythology over time. Non-Hindu deities like Kittung were added to the Vedic pantheon while the caste system was used to regulate the newly indoctrinated indigenous community, as evidenced by the Sanskritisation (i.e., brought into the Vedic canon) of the Saora priests. Where the goal of pre-colonial appropriation of indigenous cultures in South Asia was integration into the caste system, that of colonial powers was to classify societies by an alien index of development using the scientific bases of ethnography and anthropology, i.e., how deserving they were of colonial rule. This problem of misinterpreting or misidentifying indigenous practices persists in new forms today, as can be seen in the case of Jangarh Singh Shyam — a prominent Pardhan painter and the first internationally established adivasi artist — described later in this essay.

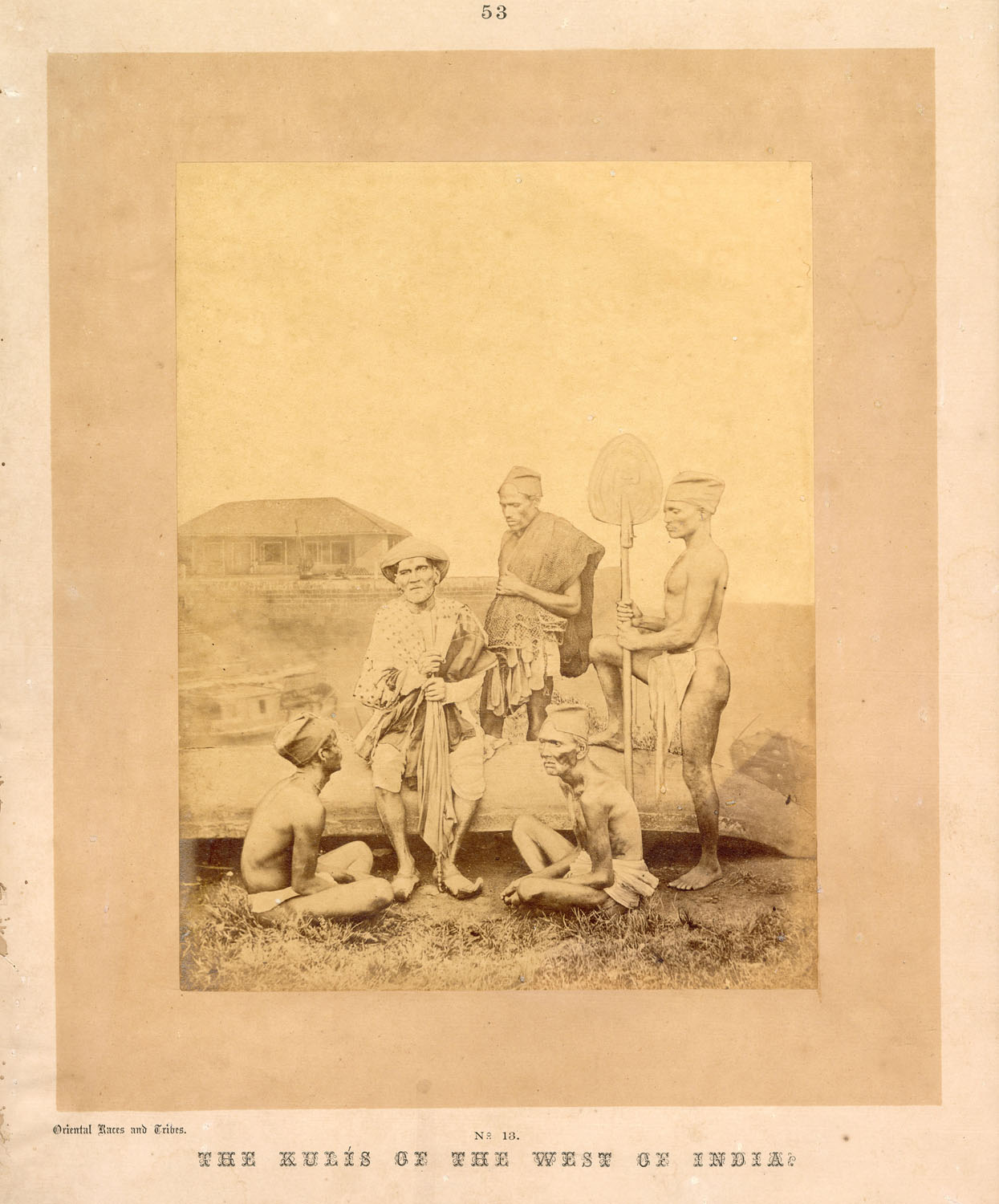

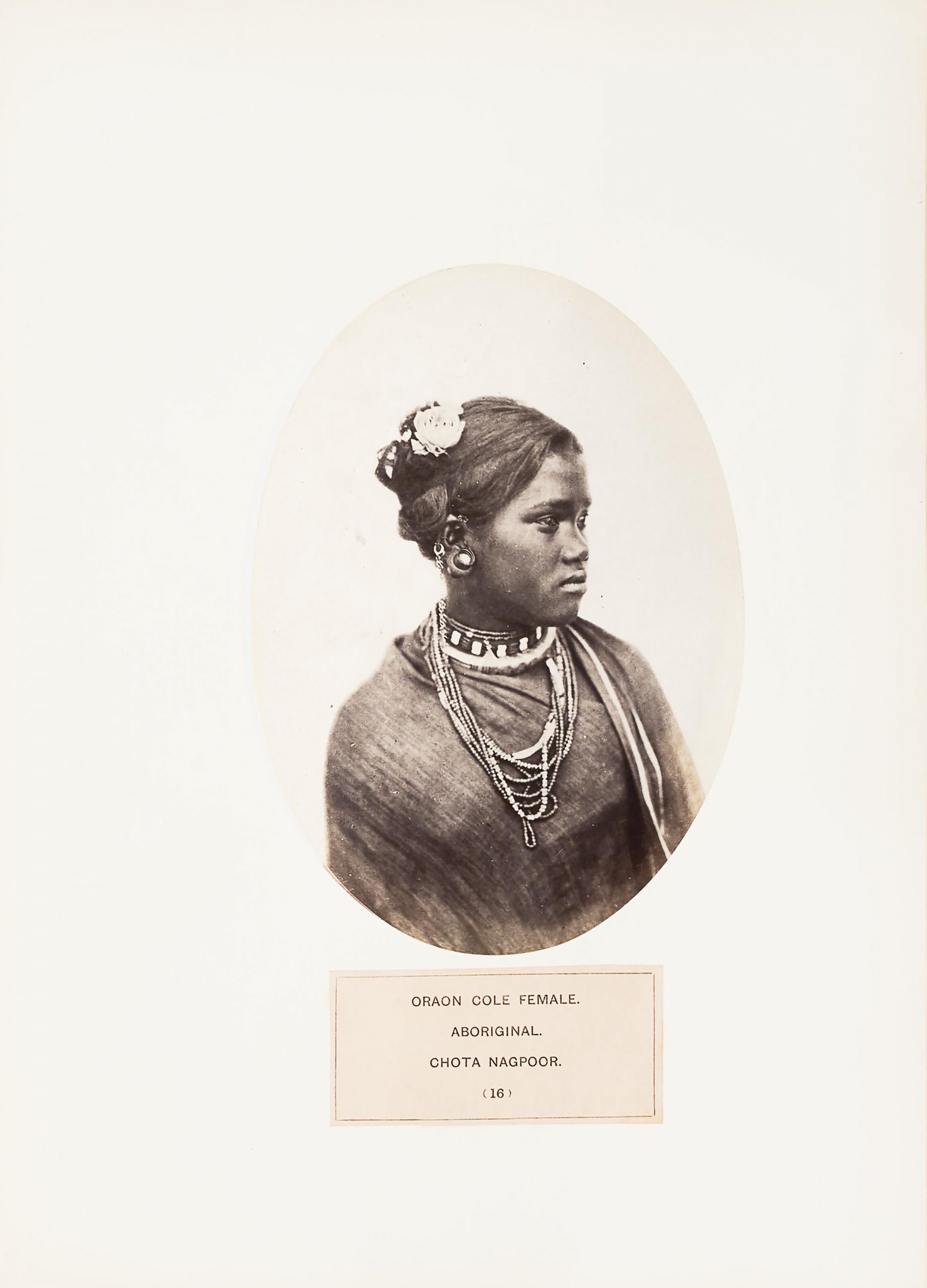

Documentation of indigenous art in the colonial period is closely linked to the introduction of photography. Prior to India’s First War of Independence in 1857, the camera was mainly used by European ethnographers to document the lives and cultures of indigenous communities, but after 1857, this was repurposed to identify tribes considered potential threats to the British rule, aided by administrative surveys such as Sir Herbert Risley and William Crooke’s handbooks on Indian tribes and castes.

Photograph from William Johnson’s The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay, 1863. Credit: Published in The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay by William Johnson (1863)

Under the assumption that photographs could portray an objective “truth” about their subject, ethnographic surveys like William Johnson’s The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay (1863) used photography for the anthropometric and racial analysis of indigenous groups.

This reliance on photographs for such analyses was an attempt to place the complex, shifting terrain of cultural practices under scientific scrutiny and thus objectify indigenous subjects of colonial rule.

Photograph of a performative work from Pushpamala N’s series Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs, 2000-2004, Sepia-toned silver gelatin print, MAP

The iconographic markers of such photographs — calipers and yardsticks aligned with human heads, frontal shots of lined-up figures and other compositional elements of anthropometric study — have been appropriated by contemporary Indian artists such as Pushpamala N and her collaborator Clare Arni to highlight the weaponisation of photography and the apathetic scientific processes by colonial agents. The lack of a recognition of individuality among members of indigenous communities is also reflected in the documentation of their art.

Even today, scholarship on these artefacts rarely refers to them as “fine art” — a term typically reserved for images made by Western artists and extended to include Western models of art-making and art display in the developing world. Objects such as traditional African masks, costumes and other ceremonial items, which were made and used in large numbers, are often described without conscious reference to the artist’s hand in producing variations on a theme. Fine art has long been considered the product of individual genius, whereas indigenous and folk crafts have been seen as the static replication of an entire community’s worldview or mythology, with the individual maker being little more than a means to that end.

Photograph of a Kol woman, 1868-1875. Credit: Published in The People of India by John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye (1868-1875)

This distorted lens, coupled with the general sense of authority felt by colonial agents in documenting, classifying and, in many cases, even criminalising indigenous communities and their unique forms of coexistence, has set the historical tone of engagement between indigenous and mainstream populations in the modern era. Although discussions on indigenous art have come a long way from their colonial roots, there remain several echoes of the colonial mindset in recent attempts by Western museums, especially in Australia and Canada, as well as in key exhibitions in India such as Vernacular, in the Contemporary (2010), to find ways of representing indigenous art in the mainstream.

Political and public representation of indigenous groups

In independent India, the colonial practice of classifying adivasi and “lower” caste groups has been repurposed rather than abandoned. Scheduled Tribes are given special rights related to land use in their ancestral regions (these are typically in forests or mountains) and cultural practices, provided with reserved seats in higher education and other such allowances, with the aim of correcting the historical power imbalance between indigenous and urban societies. The preservation of adivasi cultures is in line with India’s postcolonial vision of a “salad bowl” attitude towards cosmopolitanism, where each community retains their cultural integrity, rather than a “melting pot” model where all cultures are subsumed under a national or regional value system. Much of the intended support structures suggested by the Indian Constitution rely on good-faith actors and empathetic engagements with indigenous communities, which has historically left much room for corruption and the willful exploitation of indigenous land and resources.

Although the particulars of political representation vary from country to country, the challenges faced by indigenous people across the world involve the same three-part causes of colonial rule, industrial expansion and state-sponsored violence — as evidenced by the Naxal and Zapatista movements in India and Mexico respectively. These are essentially conflicts between urban-centric industrial societies looking to expand and those who live a parallel, self-governed existence outside of that particular idea of civilisation and have typically grown after the end of colonial rule. Such disputes — whether peaceful protests, lobbying or armed struggle — arise over the use of indigenous people’s land for resources like mineral ore, timber, oil, etc., or the land itself, to be used for infrastructure and farmland development. Exploitative projects such as overfishing, constructing dams and dumping waste can have a negative impact on the indigenous population of a region. Political scapegoating, opportunism and the rise of local militia are typical impediments on the road to peaceful resolutions, although resolutions are often brokered after mutual threats of violence, public outcry against harmful projects, or both.

Another major factor in the lack of public support for indigenous rights in India is the belief that groups fighting for those rights are either fundamentally violent or have been co-opted by forces seeking to destabilise the nation. This assumption of their “primitive” condition and naivete often comes from a lack of public knowledge on adivasi cultures — a result of institutional marginalisation that dates back to the colonial period. As a direct result, indigenous art continues to be deprioritised, leading to a continued absence of the necessary perspectives required to garner interest in adivasi culture.

The acquisition and display of indigenous art

Like many issues around indigenous rights, this cultural blindspot is related to the fact that a vast number of art objects and ceremonial artefacts made by indigenous communities across the world are presently housed in Western museums. In colonial exhibitions of these objects — publicly in the early twentieth century and in private viewings since the nineteenth century — almost all of which were looted from the places where they were made, broad generalisations, simplistic interpretations and moral judgement are also clearly visible.

An aboriginal Gweagal shield, 1770, Wood. Image courtesy: Trustees of the British Museum

The Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931, very well received by its European audience, is an example of a colonial double-speak functioning on a large-scale, giving the public the impression that the French empire was enriched — and not made culpable — by its control over indigenous artefacts, land and people across the world. Today, the murky history of how these objects were acquired is referred to only distantly using vague language, while the harsh realities faced by these communities remains unmentioned. The placement of these objects in museums while their makers continued to be subjected to often brutal colonial rule — as is the case with the British Museum’s collection of Australian aboriginal art — has continued to allow for an imagined separation of art and the communities that created it. In this regard, the European museum functioned as the public face of a scientific justification for colonial rule. Beginning with the expanded “cabinet of curiosities” at the Ashmolean Museum in the seventeenth century, and then in other collections of objects of natural and cultural history brought from across the world over the next three centuries, such as the British Museum and, more recently, the Musée du quai Branly, the museum became a space where such objects could be studied with next to no immediate context. It became a site where the inconvenient subjectivities, social histories and fluidity of indigenous culture were done away with in order that their art could be crystallised into an object-oriented ethnographic canon for European consumption, usually by an audience who had not and would not come into contact with an indigenous person.

In recent years, European and American museums have made some attempts at displaying indigenous art objects with a view to reconciling their original roots with the ways in which these objects were obtained. However, these attempts are often lukewarm, and institutions in possession of objects taken far from their place of origin find it difficult to respond to calls for their return. Museums in countries like Canada and Australia, where much of the indigenous collection is at least within its region of origin, have made better steps to adapt museums to indigenous art. In Australia and India, museums have gone further and involved members of indigenous communities to create new, non-hierarchical models of the museum, allowing for a relationship with indigenous art that is based on open dialogue. A key example of these is Vaacha, a museum in the Rathwa tribe lands between Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, which is run by members of the local community.

The relationship between Modern and indigenous art: appropriation and collaboration

Mbangu (illness) mask, Late 19th-early 20th century, Painted wood, natural fibre. Image courtesy: Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium

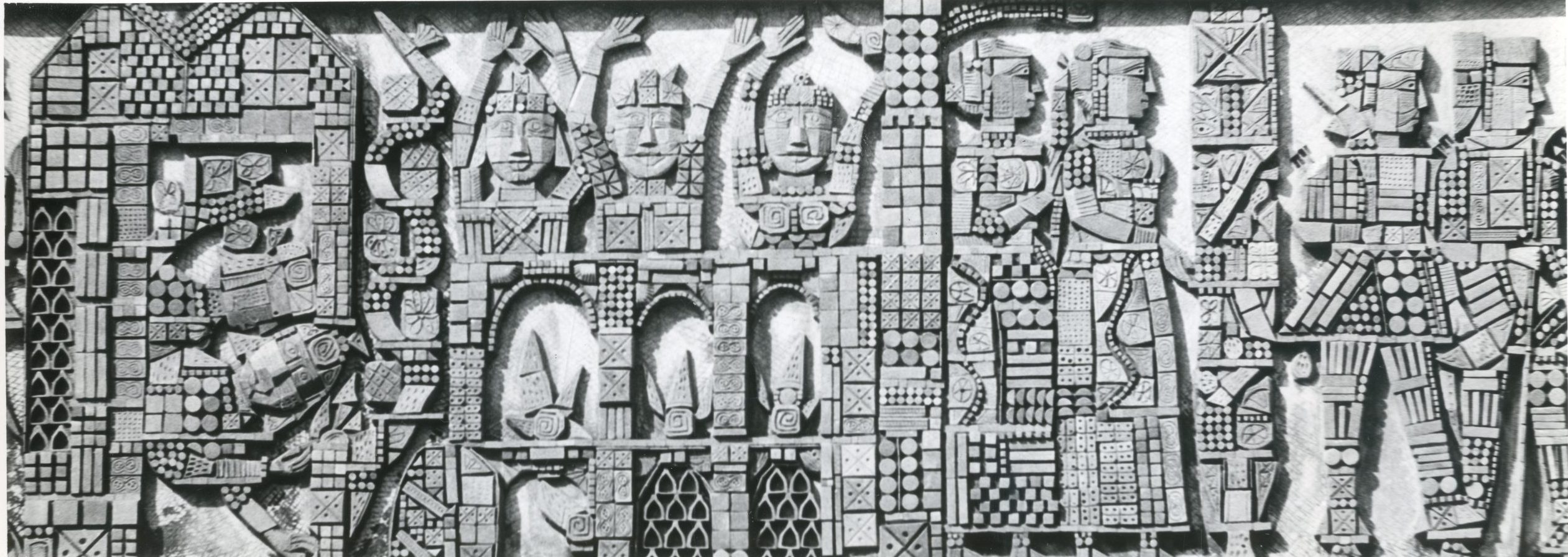

Mainstream artists across the world have often borrowed from indigenous art in a range of ways. On one end of the spectrum is the more appropriative form of influence, a famous case being Pablo Picasso’s adoption of African traditional masks (likely those made by the Pende people) in his experiments with Cubism. In the Indian context (and on the other end of spectrum) are collaboratively inclined artists like Jagdish Swaminathan and KG Subramanyan, who studied folk and adivasi art carefully and made consistent attempts to build bridges between adivasi and mainstream society, in addition to absorbing influence from these traditions throughout their careers. Their influential positions in Indian art history have thus set a positive, empathetic tone through which other artists, such as Mrinalini Mukherjee and Jyoti Bhatt, have engaged with adivasi art.

It should be noted, however, that in many ways, this inspiration is still problematic: the frequent lack of context in Bhatt’s documentation of folk art echoes the simplistic colonial consumption of indigenous “curios”, and Swaminathan’s quest to find and highlight indigenous artists to present to the art market had several unforeseen consequences, as explained later in this essay.

In the case of Swaminathan, his role as the Director of the Roopankar Museum at Bharat Bhavan — a cultural centre in Bhopal where several folk artists have worked — created a space for several indigenous artists to enter the commercial art field alongside their mainstream counterparts, not only as traditional practitioners but also as individual artists in their own right. Unlike many of his peers and other scholars, Swaminathan actively encouraged this idea of parity between lone indigenous and non-indigenous artists, which went a long way towards establishing a place in the art market, even a niche one, for adivasi and folk art. At Roopankar, where many adivasi artists worked, Swaminathan made sure to highlight the individual nature of the work produced by each of these artists. A notable example of one such artist is Jangarh Singh Shyam, whose work was made in an entirely personal style and not as a replication of Pardhan art as is often assumed.

However, these artists continue to be thought of as simply reproducing a static indigenous iconography imagined by the art market and the wider public. Despite the increasing interest in indigenous art in the past two decades — indicated by a rise in sales — collectors and middlemen have largely avoided trading in indigenous artists’ work. Part of the reason for this, some buyers claim, is the risk that the artist’s family might join in the art-making process and dilute the “individual genius” that is so highly prized in the art market — despite the fact that contracted art workers, collectives and assistants have been fairly common in art history, from miniature manuscript workshops to the Renaissance era and studios of contemporary artists like Damien Hirst.

Craft revival and the differentiation between indigenous artists and indigenous craftsmen

Due to the many points of contact between different indigenous communities, especially nomadic and mercantile ones, there is potentially a difference between what scholars understand and communicate to the public about an art tradition and what actually happens on the ground. Artisans from certain communities are hired by others to produce objects that are only used by the buyer, leading urban-origin researchers unfamiliar with these trade relations to assume that the owner and the maker of an item must come from the same community.

Swarna Chitrakar, a Patua artist from West Bengal, 2017 ,Digital photograph. Photograph by Rana Chakraborty, Image Source: Scroll.in

This was the assumption about painted Santhal scrolls for a long time in colonial India. It was later realised that these scrolls were made by travelling Jadu Patua storytellers as part of their performances for the Santhals and other groups. This often involved retelling Santhal myths and stories with alterations to suit the context or using motifs borrowed from the mainstream urban world. Such customised mutations were common and understood as elements of the storytelling craft.

This recognition of adaptability and a loose grip over cultural definitions between adivasi communities has made a historical network of interdependence and coexistence possible, the absence of which, in a modern and postcolonial society, has led to an inability to recognise such forms of co-making when we first see them.

The question of individual talent is a crucial one when discussing indigenous art and is often tied to the issue of contemporaneity. By assuming that a work of art is the product of a community’s image-making traditions while ignoring the hand of the artist, we relegate that image to a static iconography devoid of style. The very idea of style implies changes in image-making directed by the individual choices of artists. A notable recent example of curatorial innovations that incorporate this issue is the 2010 exhibition Vernacular, in the Contemporary, curated by Jackfruit Research and Design, led by Annapurna Garimella. The show reflects the push-and-pull experienced by indigenous artists divided between processes that have emerged from individual practice and their traditional art forms. Recognising the individual allows one to see indigenous art objects as the results of a compounded history of many such stylistic changes. It also allows the viewer to avoid the assumption that any single artist’s work can somehow perfectly represent their culture.

The exoticisation of indigenous art in contemporary markets

The indigenous artist, like any artist, is always affected by the larger structures of the contemporary art world within which they practice. The lingering colonial fetishisation of indigenous art, coupled with the Modern conflation between valuing and valorising individual “avant-garde” artists, has often resulted in a great deal of pressure being placed on indigenous artists to satisfy this image of their community’s cultural practices in order to remain collectible. Colonial images of indigenous people were often staged as caricatures of such communities as expected by Western audiences, such as ethnographic photographs developed by the Saché & Westfield studio in Calcutta (now Kolkata). A notable example of this is a photograph exhibited at the Paris International Exposition of 1867, showing JN Homfray in three-quarter profile with a group of North Sentinelese people positioned frontally — a very familiar composition in colonial imagery that was used to study the physical features of ethnic groups through an anthropometric lens.

Although many artists belonging to marginalised groups have been pigeon-holed into market niches, indigenous artists arguably experience this more acutely. In the case of Indian art, particularly under Swaminathan’s directorship of the Roopankar Museum, adivasi artists were “discovered” by scouts and introduced to scholars or curators, who in turn initiated these artists into the contemporary art scene, as was the case first with Bhuri Bai, then Jangarh Singh Shyam, Pema Fatya and others.

In reality, indigenous artists are subject to changes in their practice as much as anyone else. Their success in the field of contemporary art, however, coupled with them being projected as representatives of their communities — as was the case with Jangarh Singh Shyam — creates a tradition where there once was none. Jangarh Singh was erroneously labelled as an artist working in the Pardhan Gond tradition when his work was sold or exhibited, despite the fact that his community’s art tradition was aniconic and at odds with his practice. He quickly rose to prominence through a combination of the quality of his work as well as the market niche into which he was placed. Other artists, including members of Jangarh Singh’s family, began producing paintings of a similar style — not with the intent to imitate him but with an acceptance of the market’s idea of what Gond art was and how it was to be practised. This created the possibility of financial gain for the artists (albeit not the runaway success that characterised Jangarh Singh’s career as an avant-gardist) as well as validating the market’s assumptions by turning a misconception into reality towards a very practical end. The art market is thus a powerful but unregulated swarm of actors who unwittingly play a major role in making contemporary indigenous artists beholden not only to their personal careers but also to the market’s imagination of their community.

Conclusion

Although scholars and institutions in India have made good-faith attempts to bridge the chasm between mainstream art and indigenous practitioners, there is still a long way to go. Some of these problems have a clear history, such as colonisation and industrialisation. Other parts of the rift are deeper and less tangible, such as the different understandings of time, ownership and the fluidity of cultural practices. Commercial speculation, opportunism and other neoliberal structures that characterise the art market today have repurposed much of what used to be colonial ills into more heavily veiled systemic challenges to indigenous practitioners and those who consume not only their work but also the exoticism and misconstrued cultural analysis sold with it. In the few institutions where indigenous art history is taught, courses sometimes have dated information and views and fail to highlight the intersection between the cultural, political and economic histories of indigenous communities in India or the world. This static and apolitical position potentially discourages future art historians from taking further interest in indigenous art.

Given all of this, it can be said that indigenous artists are twice contemporary: first, in the usual sense of contributing to the undecided history that constitutes the present day and the present market; and second, as forerunners in the creation of an ever-evolving tradition of indigenous image-making — even if the role of representative is thrust upon them. The question of whether this agency is an unfair burden or a unique and valuable characteristic that indigenous artists bring to the table is something that the viewer will need to keep in mind when engaging with contemporary art. Indigenous populations in many parts of the world are shrinking, while the boundaries between rural, indigenous and urban cultures are becoming less distinct. The integration of indigenous people at an individual level — whether through increased access to technology or economic incentives to move to urban areas — coupled with institutional sensitivity can enrich mainstream perspectives about indigenous cultures and add a layer to their complex and shared history. We can already see this yielding fruit as more museums readjust their structural flaws and take a broader, more accommodating perspective of indigenous art. At the same time, one must note that the far-reaching consequences of colonialism, industrialisation and the illusory free market have proven to be insoluble; in the manner of indigenous communities the world over, we will have to stay with the trouble of these circumstances and remain open to the new forms of dialogue, symbiosis and synthesis that they prompt.

References

Vidal, Denis. “All for one, one for all : A new art for the Gonds” in Visual Histories of South Asia, ed. Annamaria Motrescu-Mayes & Marcus Banks. Primus Books, Delhi, 2018.

Hacker, Katherine. “A Simultaneous Validity of Co-Existing Cultures: J. Swaminathan, the Bharat Bhavan, and Contemporaneity.” Archives of Asian Art vol. 64, no. 2 (2014): 191-209.

Goldstein, Ilana Seltzer. “Visible Art, Invisible Artists? The Incorporation of Aboriginal Objects and Knowledge in Australian Museums.” Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, vol 10, no 1. June 2013. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1809-43412013000100019.

Tilche, Alice. “A Forgotten Adivasi Landscape.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 49, no. 2 (2015): 188-215.

“Vaacha – Museum of Voice.” Museums of India. https://www.museumsofindia.org/museum/779/vaacha-museum-of-voice.

Bryant, Edwin F. Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Elwin, Verrier. The Religion of an Indian Tribe. Oxford University Press, 1955.

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: an Alternative History. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Shah, Alpa. “The Intimacy of Insurgency: Beyond Coercion, Greed or Grievance in Maoist India.” Economy and Society. vol. 42, no. 3 (2013): 480-506.

Kochhar, Ritika. “Folk Theorems.” Open. December 06, 2017. https://openthemagazine.com/art-culture/folk-theorems/.

Anita Singh. “Damien Hirst: Assistants Make My Spot Paintings but My Heart Is in Them All.” The Telegraph. January 12, 2012. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-news/9010657/Damien-Hirst-assistants-make-my-spot-paintings-but-my-heart-is-in-them-all.html.

Mahima A Jain. “The Exoticised Images of India by Western Photographers Have Left a Dark Legacy.” Scroll.in. February 20, 2019. https://scroll.in/magazine/913134/the-exoticised-images-of-india-by-western-photographers-have-left-a-dismal-legacy.

Singh, Kumar Suresh. People of India. Seagull Books, 2012.

Daley, Paul. “The Gweagal Shield and the Fight to Change the British Museum’s Attitude to Seized Artefacts”. The Guardian. September 25, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/sep/25/the-gweagal-shield-and-the-fight-to-change-the-british-museums-attitude-to-seized-artefacts.