Blogs

The Wonder of Islamic Art

Krittika Kumari

Launching a brand new talk series titled The Deep Dive, that spotlights art and culture from different global and transcultural contexts, Navina’s comprehensive lecture allowed viewers to journey through centuries of Islamic art, all the while elaborating on how Islam has absorbed from the world, especially in its intellectual traditions, and how the world sees Islam.

The artistic and cultural traditions of Islam have contributed immensely to the development of Indian art and literature. On 29 January 2021, MAP hosted a virtual lecture with Navina Najat Haider, who is the Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah Curator in charge of Islamic Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Through her intriguing narrative, Navina unravelled for viewers the intellectual and mystical nature of Islamic art.

Launching a brand new talk series titled The Deep Dive, that spotlights art and culture from different global and transcultural contexts, Navina’s comprehensive lecture allowed viewers to journey through centuries of Islamic art, all the while elaborating on how Islam has absorbed from the world, especially in its intellectual traditions, and how the world sees Islam. By weaving in a selection of significant artefacts from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) in her story, Navina really unpacked the story of one of the world’s oldest religions; a story that has unfolded across the world for over 14 centuries.

She touched upon the nuances of language, interpretation and meaning when it comes to writing or speaking about Islamic history. Take for instance the belief that the depiction of human figures was prohibited in Islamic art. Navina explained that like most other early religions such as Buddhism and Christianity, Islam is an aniconic religion, which means that that for them, God has no image. Similarly, by extension, sacred figures such as the Prophet Mohammed and angels were not depicted as objects of worship unless it was within an illustrated text. Perhaps, it is because of this aniconic nature of the religion that the art of calligraphy and the use of arabesque designs gained prominence in Islamic art.

The reverence of the calligraphic art is also closely linked to the Quran being the most prestigious art form in the Islamic world. Regarded as God’s own word, the Quran and its reproduction, by memory or otherwise, soon became the highest form of artistic enterprise, whether as illuminated manuscripts or on decorative objects. In fact, the entire Quran is also painted in ink on a talismanic shirt, housed in The Met’s collection, that was made in India during the sultanate period.

Talismanic Shirt, c. 15th-early 16th centuries, Cotton, ink, gold, Northern India or Deccan. Image Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Interestingly, the use of calligraphy is also visible in artistic traditions from other parts of the world. To illustrate, Navina presented an exquisite Italian painting from the 15th century, The Marriage of the Virgin. On a closer look at the painting, one can notice the calligraphic inscription on the halos of Virgin Mary and Joseph, which indeed is a reference to the prestige of the art form, and the sacred word of Islam.

The Marriage of the Virgin, Michelino da Besozzo, c. 1430, Tempera on gold. Image Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the second part of her lecture, Navina elaborated on how Islamic traditions in a sense laid the foundation for the idea of world history. It has been argued that the Mongols, in particular, were extremely interested in the practice and commissioning of historical writing, as they were interested in writing themselves into the history of the Middle East, and to establish a sense of legitimacy within the world.

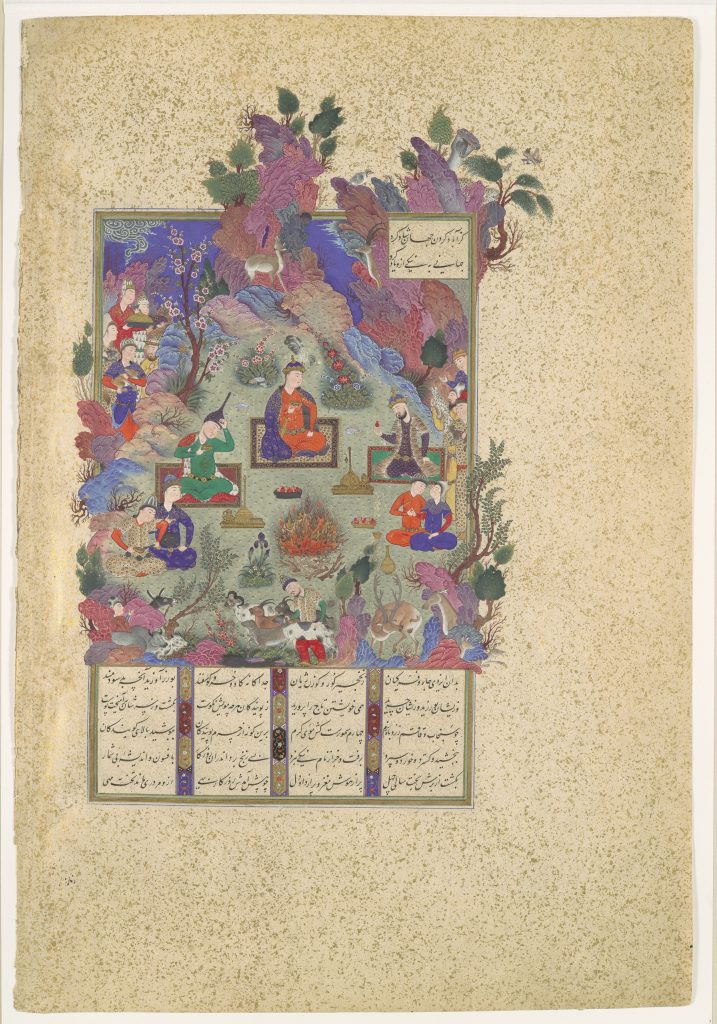

An example she cited is of the famous Shahnameh commissioned by Shah Tahmasp, the ruler of Iran during the early Safavid period and a great patron of the arts. Shahnameh was an epic that relayed the history of Persia and of all the ancient kings that ruled the region even before the Islamic conquest. Thus, it became an important convention for all Muslim kings of Iran to commission their own copy of the Shahnameh as it allowed them to establish a link to even the pre-Islamic past of Iran. Closer home in India, we observe a similar tradition in the chronicles commissioned by the Mughal kings, such as the Akbarnama, Jahangirnama and Padshahnama.

“The Feast of Sada”, Folio 22v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, Sultan Muhammad, c. 1525, Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper. Image Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

“The Feast of Sada”, Folio 22v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, Sultan Muhammad, c. 1525, Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper. Image Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is important to think of Islam as a religion that was in conversation with traditions all over the globe. Throughout her talk and with the help of wonderful examples from The Met’s collection, Navina highlighted the creativity and pictorial and intellectual innovation of the Islamic world. If you are a lover of history and art, this lecture is a must-watch and is available to stream here!

Krittika Kumari is the Digital Editor at the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru. A graduate of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, her research interest lies in the Mughal miniature painting tradition, as well as Indian Modern Art.