Blogs

Of Home and Displacement

Shailaja Tripathi

Artist Zoya Siddiqui engages with the themes of belonging, cultural memory and spatial distance.

In artist Zoya Siddiqui’s video installation At a Distance of But Two Bow-Lengths, or Even Nearer a series of shots – of her family home, the images of the Kaabah, the holiest site in Islam, flashing on TV, placed on the walls, and in cabinets appear before the viewer. The images are accompanied by a conversation around what it means to be a Muslim, between the artist, her brother and mother.

This work, that takes its name from a Quranic verse, is inspired by the 24/7 broadcast channel of Kaaba. Exploring the concept of distance and belonging, the video is part of Siddiqui’s digital exhibition at Museum of Art & Photography, Bangalore.

At a Distance of But Two Bow-Lengths, or Even Nearer, 2018, Zoya Siddiqui, Image Courtesy: Artist

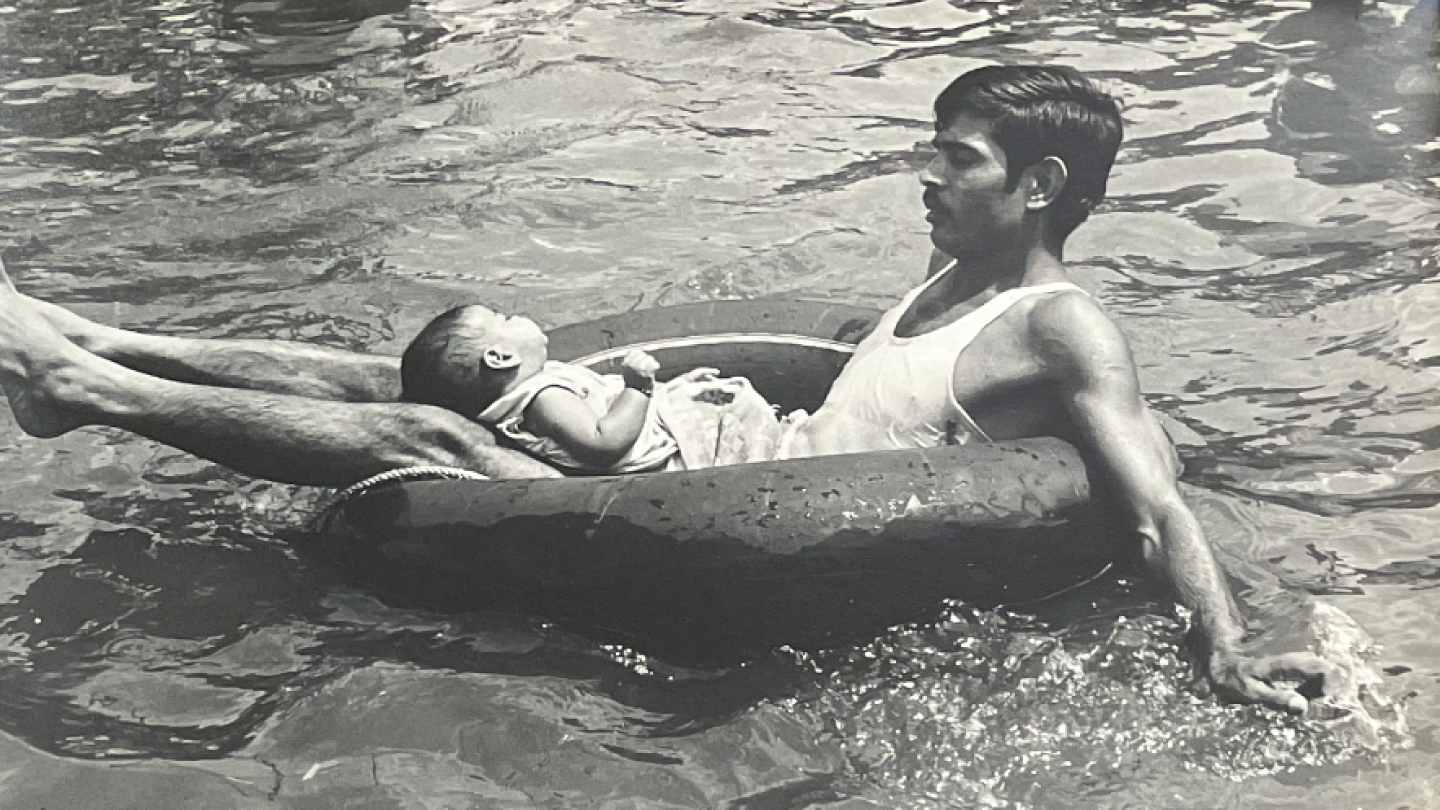

Born in Lahore, Siddiqui now divides her time between Pakistan and Canada. She has been a part of several international residencies and as part of her In-Situ residency in Lancashire, she created a large-scale installation Geology of a Home at the abandoned Brierfield Mill in Lancashire. The mill employed several Pakistani immigrants in the 1970s and when it closed down in the 1990s, the immigrants lost their jobs. Siddiqui’s video captures the live feed of the participants in the mill who came and sat on the sofa facing their projections on the screen ahead and the video is also interspersed with images of sofas in the homes of the textile mill workers. In her works, Siddiqui weaves a narrative of home, migration, displacement and cultural memory.

Elaborating on her themes, Siddiqui says, “In exploring home and belonging, I was actually looking at those who don’t belong; the ‘other’. This demarcation is a collective imaginary, a power play and also a larger systemic problem. Personally, through experiences of traveling, living elsewhere and also of having loved ones away in other lands, this ‘otherness’ became a viscerally felt experience. One feels marked; there is a barrier in empathy, language, and memory; there is a discontinuity. This discontinuity leads one to gather sources of comfort, through other diaspora or through food, material memory etc.” Being away from home herself, Siddiqui could relate to the need to identify and belong, leading her to create Geology of a Home and Melancholies of the Migrated.

Geology of a Home, 2015, Zoya Siddiqui, Image Courtesy: Artist

In her intensely personal Memoryscape video series, Siddiqui revisits the memories of her childhood. In her own words: “There was also a strong desire to revisit memories, which I related to. For my Memoryscape videos, I allowed myself to indulge in my own personal revisiting whilst living in the US, through the eyes of GPS and a drone (both technologies originally conceived for the US military), which let me navigate through my childhood homes.”

Memoryscape, Zoya Siddiqui, Image Courtesy: Artist

Seminal to her art practice is exploring the social implications of technology. For instance in her Memoryscape videos, she probes geographic distance in terms of mapping technologies, and social distance in terms of being an outsider. The artist explains, “GPS and drones are two of many mapping technologies, originally designed for the US military, that mark an individual with a removed God-eye, especially those from developing countries such as Pakistan. In my videos, I subverted the technologies’ inherent apathy by using their eyes to look for places of deep, personal significance from my childhood in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia; I walked the camera in real-time through these spaces whilst narrating what the eye of my memory saw, exposing the technology’s limitations.”

The pandemic unleashed a crisis highlighting the issue of migrants, displacement, homelessness. But artists like Siddiqui have been dwelling on the subject of displacement for long. “For all my works mentioned above and others, there is a political undercurrent; migrations are more often than not a re-enactment of global power dynamics and a reassertion of hierarchies.”

In her two decades of experience with print and electronic media, Shailaja has focused on the world of art through her writings. Based in Bengaluru, India, she remains committed to the idea of bridging the gap between art and people.