Blogs

Leafy Rhapsodies and Culinary Landscapes in Northeast India

Rini Barman

Packing and wrapping what we eat is deeply tied with our souls and leaves have a way of keeping that fragrance alive.

consider the path of a falling leaf the distance in between the branch and the earth the slightest breeze could alter its course now

consider yourself as that falling leaf falling falling and where did you come from and where are you now.

-Truong Tran, 2002

Six year old Rashmi, my cousin, is sitting under the shade of a Bokul tree and playing a game. She is collecting the dried Mimosops elengi leaves from the ground and wrapping the ovoid berries with it. Imitating the elder female folks in her family who are excited, she doesn’t know why banana leaves are laid out in the sun. And what’s the occasion? Why can’t she touch them? Her mother sternly voices from inside the kitchen: those will wrap the rice cakes tenderly as they undergo steam, an interaction with boiling water.

The origins to leaf wrapping are quite old and unclear but is widely practiced in many parts of Northeast India and countries of SouthEast Asia for cultural, ecological and medicinal reasons. The flavour profile of leaves is significant too — it imparts an unique aroma and taste into the food it is wrapped with. Back when disposable plates made of plastic were not ubiquitous, fresh leaves were used to pack both cooked and uncooked food, meats included. Some are heated first on the fire so as to ensure crispness that is essential to hold the contains inside the wraps. No matter how small or big these are, the fact that they are served, exchanged, gifted and shared marks a symbolism tough to express in words.

Ritual offering dish, c. 1750, Copper alloy, SCU.00615

I often think about the tactile aspect of wrapping and if there’s some conversation between the food and the leaves before it enters our bodies; or of practices that are alive among many ethnic groups of the region. What can we learn from them? How do centuries old techniques of packaging remain relevant at a time when plastic and other inorganic materials dominate online food package deliveries?

Last year, I was fascinated with a common Khasi sweet rectangular rice snack, called Pu Sla. The preparation entails mixing non-sticky rice that’s pounded with mortar and pestle to which jaggery mixed with warm water and a pinch of baking soda is added. The Slamet leaf, better known as Phrynium pubinerve, is used to wrap the mixture in small portions until the contents are steamed well.

Slamet is known as Koupaat in Assamese, Bolgota in Garo and Ekkam in Adi. The Tai tribes use this distinctly aromatic leaf to prepare khao toum — glutinous rice wrapped like a roll and held tight with a thread on top. It is then dipped in water and kept for boiling. In most areas, these preparations are also called tupola bhaat — tupola literally meaning a package, a parcel. Another leaf called Torapaat, possibly belonging to the ginger family, is also used to wrap meats and rice apart from the commonly used plantain leaves (kolpaat).

Pork packed with Torapaat leaf, a plant of the ginger family, Image credit: Ranjan Raktim

“Leaves that are broader are convenient in order to wrap food, so the size was traditionally kept in mind among most communities”, shares Priyadarshini Chatterjee, a Kolkata based food writer “Flavour is a big component too apart from the ingenious methods of filling and encasing. The leaves, sometimes edible themselves, also contain medicinal properties. In the Northeastern region, the richer biodiversity of leaves adds edges to foods in more ways than we can imagine,” she adds.

One also needs to understand that changing topography can bring about not just aesthetic transformations in leafy wraps but also that of how these leaves might alter in taste. In Tripura, a special leaf-wrapped rice cake called awan bangwi is made with utmost care. It usually contains glutinous rice, onion, ginger, ghee, raisins, pork, and dry fruits like nuts. Pork bangwi is also made and the leaf used is known as lairu, from the curcuma family, but its origin is uncertain. These are conical shaped and quite a feast to taste.

“Among the Dimasas, lairu which is kind of a wild turmeric plant, was used in the olden days to wrap salt and fermented fish”, comments Kanak Hagjer, on the abundance of these leaves in the hills of Dima Hasao. “One of the ancient packing styles, smaller fishes are also wrapped in leaves as well as leafy greens. Some of it is visible in the nearby local market where Naga women for example tie akhuni (fermented soyabeans) in leaves for selling”.

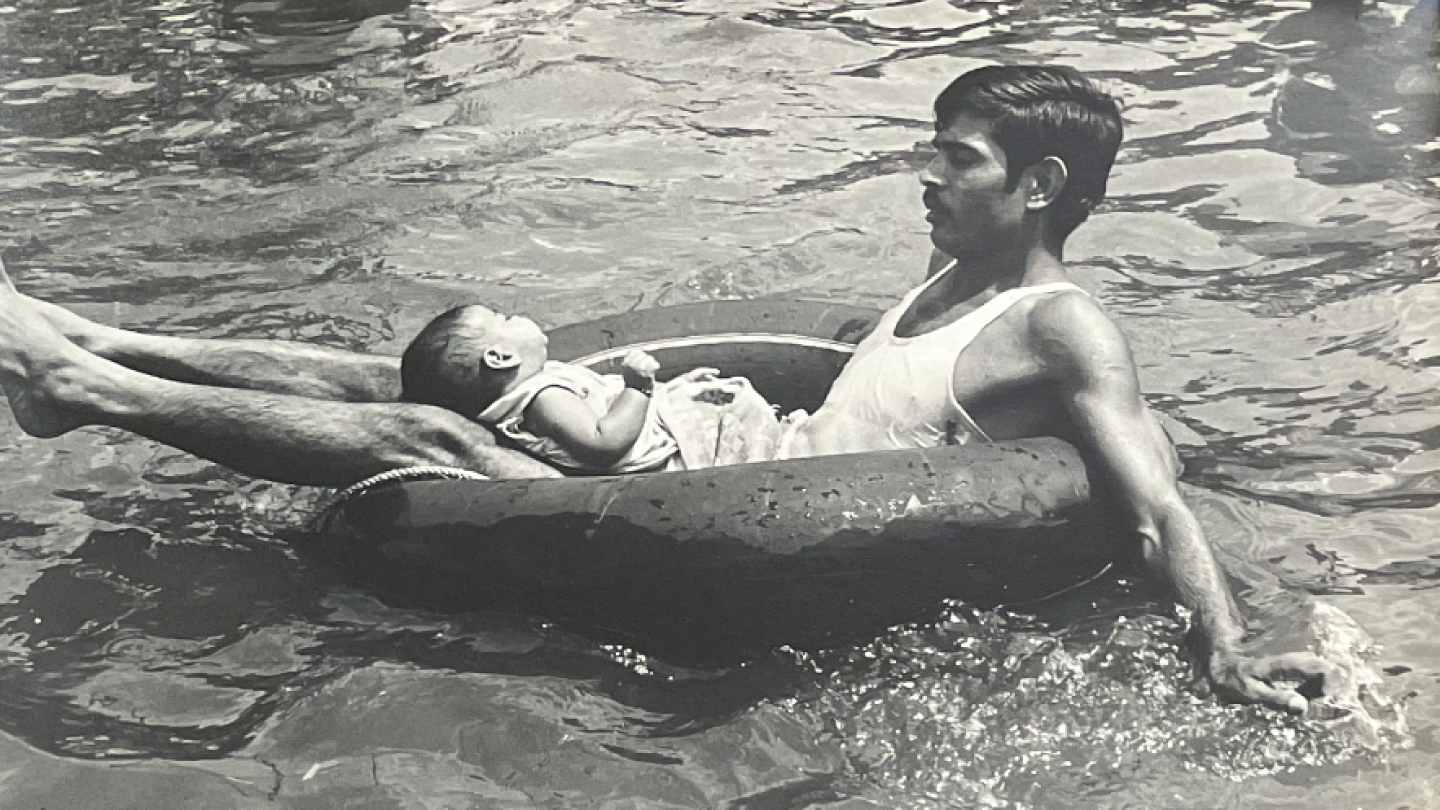

Image credit: Rajashree Konwar, Guwahati

If among the many culinary strands of social and political “differences”, we look at leaves tying the northeastern region together, we can create some new forays into cultures and ethnicities. For we often tend to forget about the subterranean power that lies in learning to hold fragility together.

From a little distance, I observe my cousin’s willingness to tie some of the rice cakes herself. She asks her mother for the thread which too is made from the banana leaf’s midrib or even slicing the stems. As her mother keeps emphasising on the grip of the wrap, I think of it as also a linguistically rearranged variant of warp. There are also stories about the act of “wrapping” being closer to its German variant raffen, meaning to pile on or even to gather.

Could it be that these kinds of ties keep piling on and make our foods richer? The aroma of leaves and the souls they enable wrap can be truly irrevocable.

Rini Barman is an independent writer and researcher based in Assam (India). She is interested in arts and culture, ethnicity, folklore of Northeast India and tweets @barman_rini.