Essays

Invisibilising the Visible: The Making of the Art of Kantha in Bengal

Brishti Modak

The essay attempts to position ‘kantha’ as an art object and to trace the trajectory of textile artisans, whose voices and art have both been left outside the paradigm of art historical intervention.

The Government of India abolished the All India Handloom Board on July 27, 2020, and again on August 3, 2020, abolished the All India Handicrafts Board. These platforms served as a regulatory body, where the artisans and representatives of the textile industry could raise their particular issues to the Government and its authorities. Whether this move muffles the voices of the artisans and further destabilises their agency has probed me to look into ways in which the inherent politics of governance affect the landscape of textile art in India. And further necessitated me to introspect the status of the ‘artisan’ in Indian art history. This essay aims to look at the cultural politics of ways in which we conceive art in India within the boundaries of the ‘modern’ and push artisanal practices to the periphery.

By attempting to position ‘Kantha’ as an art object, this essay intends to situate material culture into the discipline of art history. While doing so, I wish to trace the trajectory of textile artisans, whose voices and art have both been left outside the paradigm of art historical intervention. While there are art-historical writings that have attempted to confront this problem, by bringing the artisan to the forefront, the question of textile artisans has been largely kept outside the scholarship of art history. The art of embroidering is largely spoken within the feminist perspective, as in Rozika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch, where she looks into ways in which the hierarchisation has led to embroidery being relegated to an inferior position due to its association with domesticity and femininity. That the art of embroidery is fundamentally one that helps the women retain their agency is particularly highlighted in her text. My essay offers to take a slightly different route by not discussing Kantha through religious or the feminist lens, although the latter is implicitly located within the discussion (even if not outrightly mentioned).

Shared Culture, Divided Art Histories

The history of Kantha in Bengal is inextricably intertwined with the Partition of Bengal. Niaz Zaman in her seminal work, The Art of Kantha Embroidery, takes us through the trajectories of Kantha within Bangladesh. Kantha, as a shared traditional practice faced a dilemma due to the Partition such that it became necessary to formulate a cultural identity based on this ancient traditional art form that played a prominent role in the history of Undivided Bengal. Katherine Hacker also speaks about how the idea of kantha located within ‘Undivided Bengal’ serves as a “utopic ideal but also a polemical framework to claim the historical significance of the collection”. The history of Partition further complicated the narrative of Kantha art in West Bengal. This is because Partition divided culture across geo-political lines, which brought in questions of cultural heritage and national identity. Much of the kantha works of the 19th century and early 20th century that are available in Gurusaday Museum and some in Indian Museum are from the districts of Bengal like Jessore, Khulna, Rajshahi etc, all of which are now part of Bangladesh. After the year 1971 (Bangladesh Liberation Movement), kantha art was revived in Bangladesh with the efforts of organisations and initiatives by the artist Zainul Abedin who was committed to the folk art idiom, who also played an important role in the setting up of the Folk Art and Crafts Foundation in Sonargaon. This showcases a national consciousness of Bangladeshi art that sought to create a cultural identity that was intricately related to the tradition of Bangladesh. West Bengal, on the other hand, faced a crisis in relation to Kantha because the remaining artisans were migrating to East Bengal in search of better opportunities and because of the lack of involvement of initiatives to promote the declining art of Kantha. Kantha revivalism in West Bengal started taking shape in the 1980s and the Kantha artisans in West Bengal were either refugees from Bangladesh or rural women (in West Bengal) in search of livelihood.

In this process, non-governmental organisations like SHE and Karma Kutir intervened in the Kantha revivalism project. In talking about the NGO intervention, Niaz Zaman points out how it was both beneficial and problematic for the Kantha makers. While the artisans started using newer narratives by depicting social issues such as birth control or women’s position in the family, Zaman emphasises the ways in which these narratives were still structured by the NGO workers. Hence the power dynamics between the designer and the artisan is always unequal. The Kantha makers remain anonymous, while only her craftsmanship gets highlighted. Whether this form of invisibilisation is a recent phenomenon with the influx of the circuit of designers and entrepreneurs formulates an important argument. The problem with this kind of invisibilisation is that the artisans are enfolded into a space that structurally prioritises the elite Indian as their representative. Another form of invisibilisation occurs in terms of minimum rate of daily wages, which is decided by the Labour Department. Under this department, in the State of West Bengal, there is no separate category demarcated for the textile artisans. Because of which it is upto the employer’s discretion to set up a minimum wages rate for the textile artisans.

Kantha Clusters

Kantha, which has been historically associated as a domestic artistic tradition, also has its roots with patronage in earlier centuries. The dilemma today is that Kantha works are largely dependent on the market forces, which determines the aesthetic of Kantha stitch today.

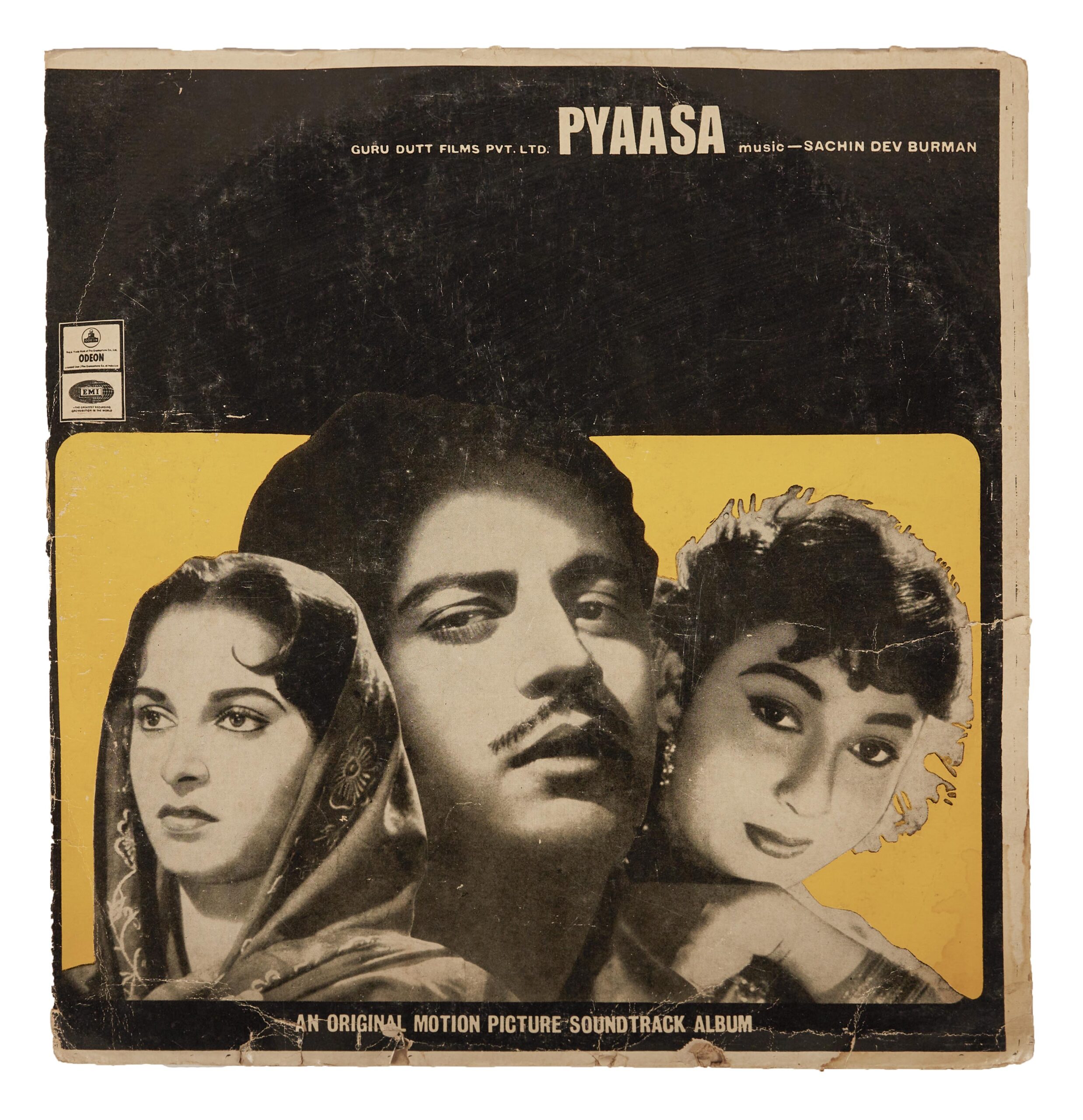

Mohenjo-daro design. Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity. Source: SASHA

We rarely get to see the works of the artisans which remain outside the market-oriented space. Thus, I wish to bring the two varieties of Kantha, both commissioned and self-use, into this study and attempt to understand whether there are distinctions at play.

When the works are commissioned, the Kantha artisans have to work within the boundaries of motifs already outlined by the buyers and are relegated to the task of replicating the original piece, like the Mohenjo Daro design, made by the artisans of Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity1 was commissioned as a replica of a Kantha exhibited in The Calico Museum.

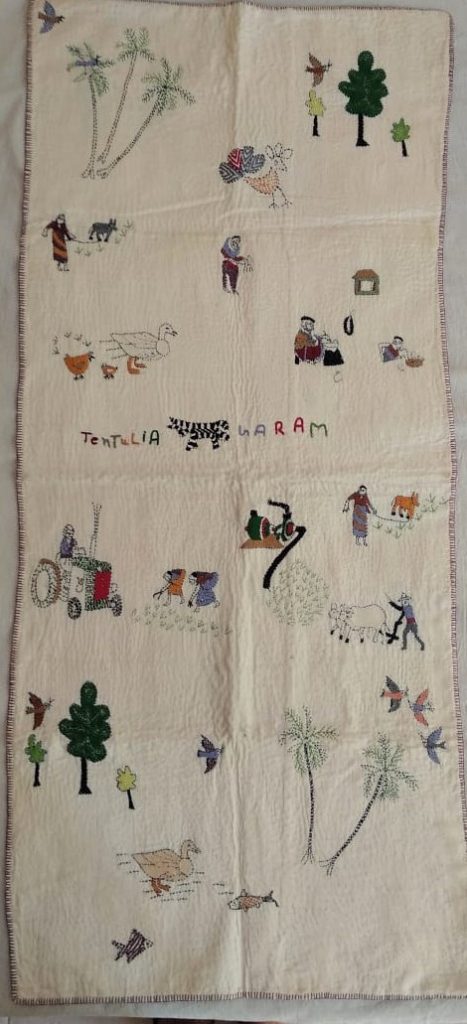

But when it comes to Kantha made for self-use, which narrates their own stories or are inspired by their surroundings, there was a certain freedom, outside the limitations of market value and labour politics, that can be seen in the work by Tantulia Kantha Shilpa Samity2, Tantulia Gram, which depicts life in the village of Tantulia, and uses unconventional motifs of tractor, irrigation pumps and sewing machines in Kantha.

Tantulia Gram, made by the artisans of Tantulia Kantha Shilpa Samity (non-commissioned). Source: SASHA

Also, there is no structured composition or fixed measurements that need to be maintained (which would have been the case if the work was commissioned by a buyer) Similarly, the artisans of Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity wanted to create a Kantha depicting the history of their organisation. This particular work shows the origin of their samity when Mother Teresa (during the floods in Panchannagram) had provided them with financial support to train refugees of partition in tailoring and weaving activities. The particular work, depicting the history of Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity was meant to be given as an heirloom (although they were unable to do it and hence commissioned another samity to do the work) to their next generation. This further brings forth another issue pertaining to the future of the art of Kantha, due to the reluctance of the next generation to go into the textile industry because Kantha-making is a laborious task and the compensation is low.

Kantha, depicting the origin of Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity. Source: SASHA

In talking about artisanal labour and agency, the question of the existing hierarchies between art and craft are often foregrounded. But rather than putting up an antagonistic relationship between art and craft, it might be more productive to engage them in a dialogue with one other.3 With the internationalist approach, Kantha has attained a position in the global platform, which has gradually produced a change in the contemporary art scene.

Left: Artisan using the quilting technique. Source: SASHA, Right: Kantha embroidery by London-based artist, Ekta Kaul. Source: Vogue India

With that, the figure of the textile artist has emerged. For instance, the London-based artist, Ekta Kaul creates embroidered StoryMaps, thus contemporarising the art of embroidery. But the stitching techniques and much of the colour palette remain rooted in the traditional art of Kantha and share a striking resemblance with one other. The stories that they tell are different based on their specific localised experiences, but it is important to bring these forms of Kantha making into dialogue through the materialities of cloth, thread and rags, that fundamentally make up the art of Kantha.

Left: Kantha made by the artisans of Tantulia Kantha Shilpa Samity. Source: SASHA, Right: Kantha embroidery by London-based artist, Ekta Kaul. Source: Vogue India

In making the visible legible, I wish to outline how the relation between drawing and stitching contributes to the making of a Kantha. Drawing an outline curtails the creative space of the artisan; since she is required to do bhorat (filling) and in doing so she is supposed to follow the sketch outlined for her. Thus, artisanal labour attains a constricted space. What we see are traces of traditional stitching patterns such as darma, dhanchari, maach maachi, golok dhanda etc., but due to the intervention in terms of design outlining and thematic directions, the artisanal works have now attained a status of a marketable product. We see glimpses of their creativity in their own works, when it is not mediated by third parties. Questions of collective labour in dialogue with individual labour, and concepts of recognition, agency, and livelihood, all remain implicitly located in studying the art of Kantha. There are disciplinary challenges that are posed to textile art, but the “museumisation” of Kantha may offer one way to resolve these complexities. By situating Kantha in a space that exhibits culture, one can propel a conversation that attempts to include all makers, irrespective of the existing hierarchies.4

Brishti Modak is an M.Phil Research Scholar at Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta and she completed her Masters in Art History from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Her research interests include 20th century Modern Indian Art; Art Theory; Aesthetics; Art pedagogy; Exhibition histories; Materiality; Print culture; Feminist art practice; and Postcolonial theory.

References

1. Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity started in 1978 and registered in 1983.The women of Tiljala Panchannagram Mahila Samity are refugees from Bangladesh who settle in Panchannagram (Kolkata). I spoke to one of the artisans, Sumita, who spoke at length about the history and art of Kantha but the memory of the Partition has not been featured in her works. Some of the core artisans in TPMS are Shibani Majumder, Smriti Mridha, Swapna Dhali, Namita Dhali, Bulu Hira.

2. Tantulia Kantha Shilpa Samity, which started in 1983 and was registered in 1996. Amina Bibi, who started the Tantulia Kantha Shilpa Samity (Barasat, North 24 Parganas), used to refer to Kantha as ‘Kaamshelai’ in her initial years. The idea of Kantha as shilpa was not yet conceived by her since this was considered as a women’s handiwork. She truly understood its artistic potential when she began travelling to exhibitions that were organised by SASHA. Presently, she is sick and was unable to talk to me but her cluster continues to work, under the supervision of Akleman and later Monirul Bibi.

3. I would like to acknowledge Prof. Parul Dave Mukerji for her feedback on my paper during the online post-graduate conference, ‘I was looking High and Low: Towards a Redistribution of the Sensible’ organised by Jawaharlal Nehru University, held between 11th -13th March 2021.

4. I would like to thank SASHA for giving me access to information regarding the Kantha clusters and also for sharing images of the Kantha works with me. Since both the artisan groups are part of SASHA. This research is an ongoing work that required museum visits and collecting archival sources, all of which has been interrupted due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Once I am able to collect all the archival materials, I hope to develop my work further, looking at all the intricacies implicit in the making of the art of Kantha.

Bibliography

Hacker, Katherine. In Search of Living Traditions. Edited by Darielle Mason, Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2010.

Mathur, Saloni. India by design: colonial history and cultural display. University of California Press, 2007.

Parker, Rozika. The Subversive Stitch Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. 1984.

Thakurta, Tapati Guha. Artists, artisans and mass picture production in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century calcutta: the changing iconography of popular prints,. vol. 8, SOUTH ASIA RESEARCH, 1988.

Thakurta, Tapati Guha. The making of a new ‘Indian’ art: Artists, aesthetics and nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850-1920. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Zaman, Niaz. The Art of Kantha Embroidery. University Press Limited, 1993.