Blogs

Art for Community

Mehreen Yousaf

Reflections on the works of IARF grantees Ashis Kumar Palei and Mayuri Chari.

In June of 2021, MAP in partnership with 1Shanthiroad Studio launched a relief fund to support artists and their work during the difficult times posed by the Covid 19 pandemic. Open to all practising artists in India, the relief fund received an overwhelming response with over 1000 applications. Twenty artists were selected by an independent jury comprising Paula Sengupta, Radha Mahendru, Indrapramit Roy and Suresh Jayaram. The jury members also offered mentorship conversations to the artists.

In an attempt to showcase the exciting work that was achieved under this grant, we have placed the grantees and their artworks in conversation with each other, to respond to and facilitate a conversation around the common themes or concerns addressed in their art.

Mayuri Chari lives and works in Goa. Her practice examines the female body as a contested site of control – how specific notions of womanhood are enforced, relegating women to the periphery. She re-appropriates the Portuguese practice of trousseau stitching, using it as a means to stitch her own body onto cloth. Trousseau stitching was adopted by communities in Goa during the Portuguese colonisation. Traditionally, women who are to be married build trousseaux to showcase on the eve of their wedding. The practice came with its own demarcations of class and caste: a self-made set was considered a great attestation of skill. Through her work, Chari reinforces the practice as one that requires great skill and mastery but uses it to subvert patriarchal representations of women and their bodies.

Image courtesy: Mayuri Chari

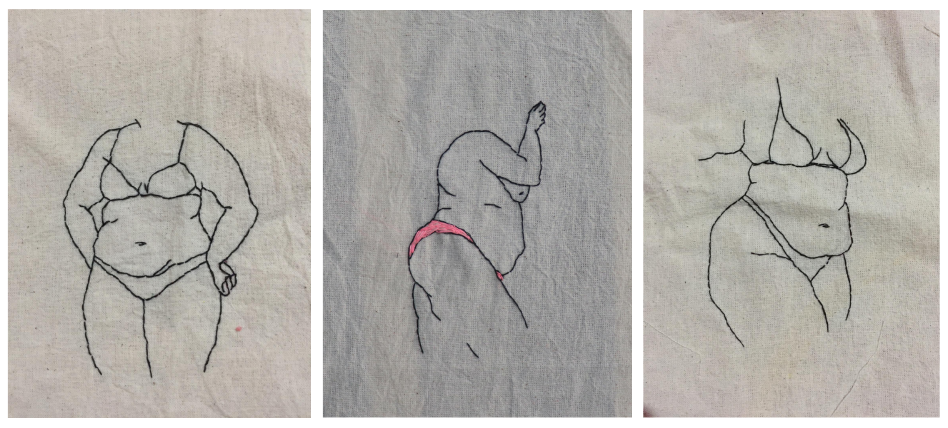

For the India Artist Relief Fund, Chari continued work on her ongoing series I WAS NOT CREATED FOR PLEASURE. The series examines how women are considered as second-class citizens – existing only to serve male desire and pleasure. The first set under the series features drawings and stitchings on paper and cloth. The female body and all its intricacies are emphasised here; these drawings capture unrestrained forms, marking each crevice and fold with meticulous detail.

I WAS NOT CREATED FOR PLEASURE (13, 14, 15), Mayuri Chari, 2021, Stitching on Cloth, Image courtesy of the artist

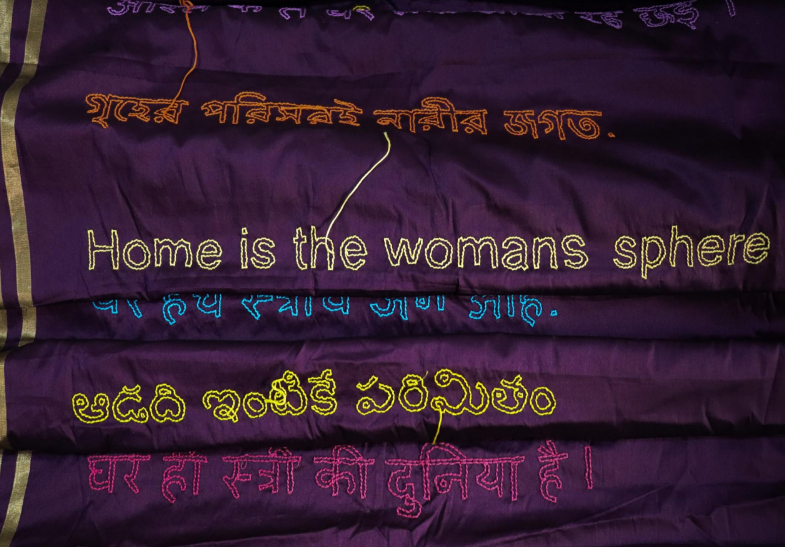

The second set in the series titled Home is a woman’s sphere portrays the anguish of women confined to domestic spaces: it records the statement in fourteen languages woven onto a saree. Through this work, Chari challenges the diktat and draws inspiration from the poetry of the great Savitribai Phule – “awake, arise, educate, smash traditions, liberate.” She examines the unspoken servitude expected of women in a household, understanding it as forced labour.

Home is a woman’s sphere, Mayuri Chari, 2021, Stitching on silk saree, Image courtesy of the artist

The third set titled Hau, Ghar Ani Ranchikud was a public project where Chari invited around fifty women from different parts of Goa to create a collage on cloth featuring stitchings, drawings, paintings and found objects. Hau, Ghar Ani Ranchikud is a phrase in the artist’s native language, Konkani, that translates to me, home and the kitchen. This collaborative work sprang out of the extended lockdowns imposed by the Covid 19 pandemic – if and how these periods of forced confinement exacerbated or alleviated expectations of informal labour carried out by women. While some found room to experiment and create during the lockdown, treating their home and kitchen as a laboratory, others found it akin to prison as their workload increased. Through reflecting and creating work, Chari enabled the participants to think critically about how they felt in being confined to the domestic space. Invoking Savitribai Phule again, the artist believed that the true road to emancipation lay in awakening the memory and creating self-awareness. The public project was accompanied by workshops where the women gathered and held discussions to unpack how they felt, and shared experiences.

Hau, Ghar Ani Ranchikud (Me, Home and The Kitchen), Mayuri Chari, 2021, Cloths, stitching, drawing, painting, found objects, Image courtesy of the artist

Chari’s work is expansive in nature and critiques the patriarchal social system and the moral code affixed to women in India through multiple lenses. The artist primarily uses a medium that is understood as an increasingly gendered activity associated with domestication and flips it on the head to express feminist dissent.

Artist Ashis Kumar Palei hails from Chandanpur, Orissa. As a Dalit, their practice investigates questions of identity, discrimination and caste inequality. Palei views the visual arts as an effective intervention to understand how caste hierarchies are perpetuated in our code of conduct.

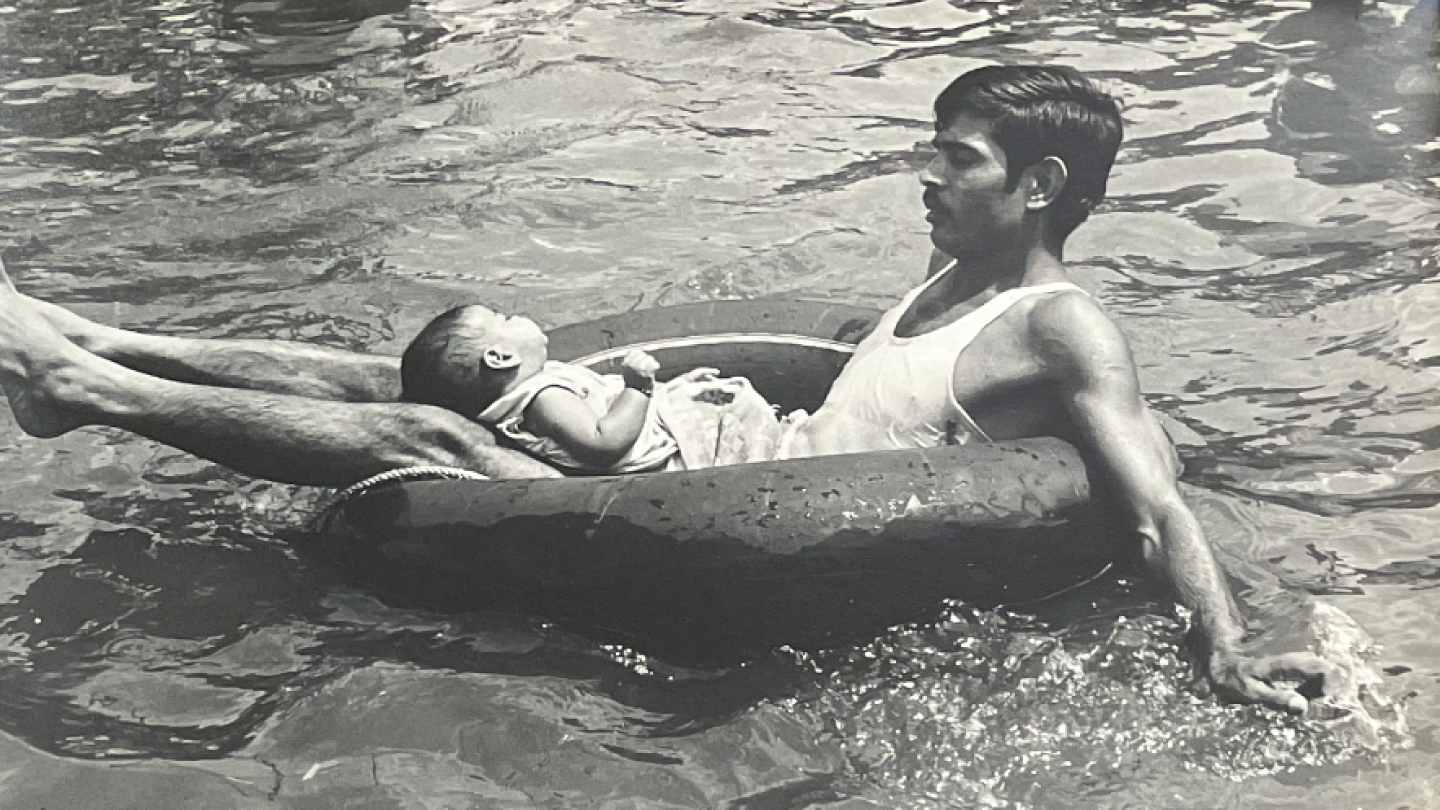

Image courtesy: Ashis Palei

Palei primarily works with mediums such as soil, bomb stick, cow dung, terracotta and paper. When speaking about the use of soil and clay in their work, the artist states that the soil is an identity marker for the marginalised. Brahmanism perceives soil as a polluting force and their traditional occupations are never linked to working with the material, it is often landless labourers, field workers and farmers who belong to marginalised communities who toil in mud, ascribing symbolic meaning to the material.

For the India Artist Relief Fund, Palei worked on a large-scale sculptural project titled Dalit Lives Matter. The sculptural work creates a village with roofless mud huts shaped in the form of Odia alphabets, with unique motifs painted on some walls. The artist states that the village in itself is supposed to act as a site of protest for the community members to gather, visually engage and respond to the work. On completion of the village, Palei invited community members and conducted a reading where they recited poems of resistance from Odia literature.

Dalit Lives Matter, Ashis Palei, 2021, Image courtesy of the artist

The bird’s eye view of the project shows the sculpture of a lifeless body of a woman in one corner, her genitalia covered in black ink. It portrays the increased rates of hate crimes targeted against Dalit women – the sense of impunity with which they are committed, as historically proper investigation and conviction rates have remained abysmal.

Dalit Lives Matter (Detail), Ashis Palei, 2021, Image courtesy of the artist

On the other end, one notices the sculpture of a woman, a blue flag in hand and depicted in motion. The colour blue is a visible marker of the Dalit protest: it is contested that the colour signifies the sky and that under the vast sky everyone is believed to be equal. In their work, Palei has found expression in these age-old identity markers but responds to localised concerns in a language that is familiar to his community members to ensure that it continues to act as a site of engagement for them.

Artists Ashis Kumar Palei’s and Mayuri Chari’s works are inspired by the communities they are part of; they look at the question of identity and invite members of their community to think critically about discriminative forces that operate within society. Through collaboration and active participation, they facilitate social, political and cultural discourses that echo in places beyond the sites of their works.

Mehreen Yousaf is an Events Coordinator at MAP. She loves listening to music and curating playlists for her friends.