Blogs

A Cuisine Born Through the Whims of a King

Sharanya Deepak

Read about the culinary legacy of the Awadhi kingdom, which was a confluence of trade, travel and art that flourished through the Indian subcontinent before the advent of the British.

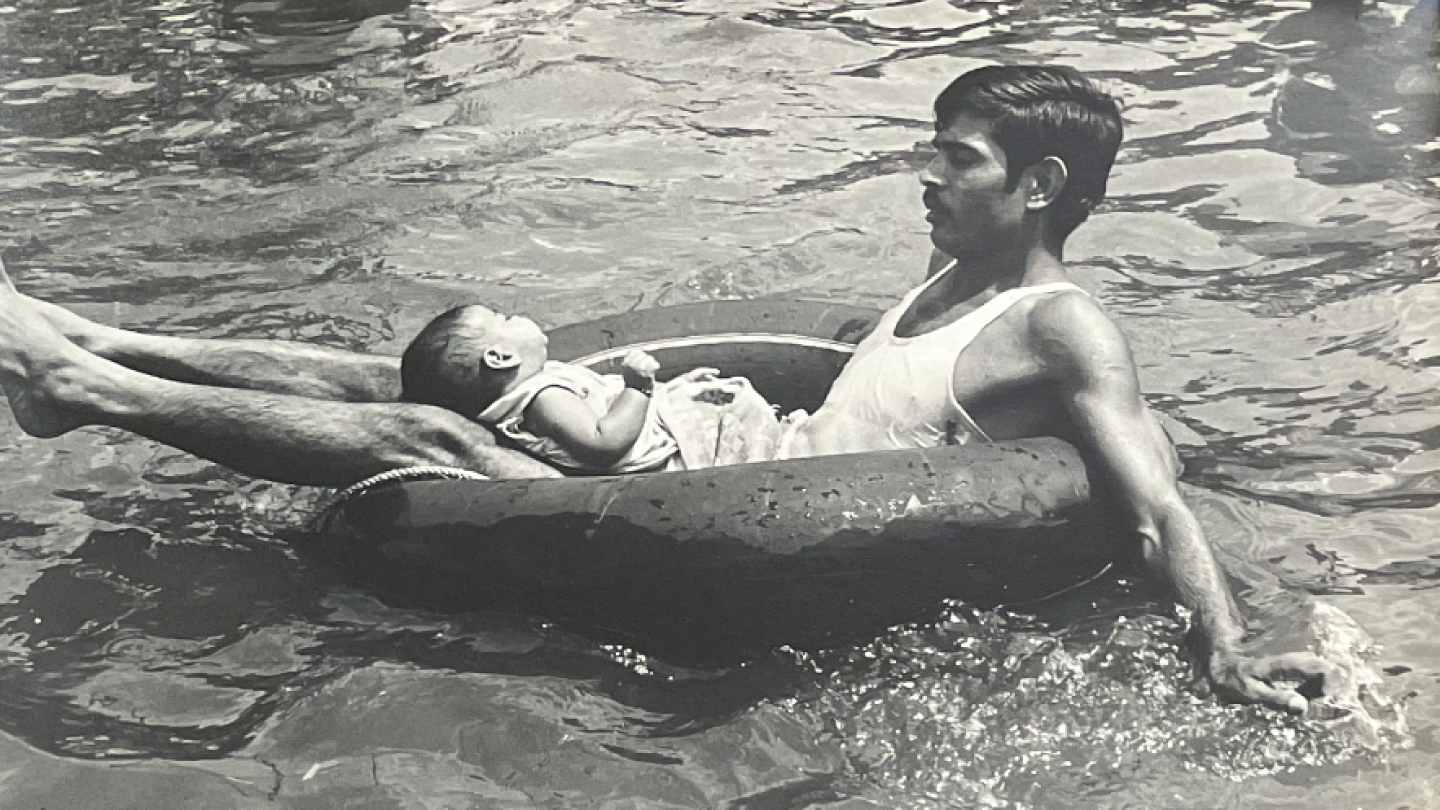

In 1856, when emperor Wajid Ali Shah fled his palace in the kingdom of Awadh from the British annexation of his territory, with him left his many wives, courtly animals, but also more than a thousand khansamas and bawarchis – trained, able cooks of the royal kitchens. There are accounts of Ali Shah embarking at his refuge in Calcutta, in whose neighborhood called Metiabruz, he would set up a microcosm of his empire, replete with bazaars, mehfils and kitchens of his erstwhile, crumbled courts. Matiaburj would turn into a thriving neighborhood, and known throughout the Eastern city for the culinary wonders of Awadh. Quormas of the Shah’s preference were served to curious visitors in his exiled courts; stalls for soft Galouti kebabs and large pots of shab-deg began to adorn the streets of Calcutta, stewed overnight, and scenting the walls of the city with meat, spices and ghee. Even Calcutta Biryani, a luscious affair of rice, meat and potatoes, was born at this moment, the addition of potatoes and mustard oil slowly making their way into the original recipe. Despite the fall of its last nawab, Awadhi cuisine lives on in the old cities of Lucknow and Kolkata, and remains tucked away in recipes, and memories of homes across South-Asia.

An engraving of Wajid Ali Shah from 1872. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Instituted in 1722, Awadh, or Oudh, has been known throughout the world for its lasso on cultures across the Indian subcontinent, Central-Asia and the Middle-East, and its kings’ keenness of cultural spheres like theatre, music, and cuisine. The culinary legacy of the kingdom is a confluence of trade, travel and art that flourished through the Indian subcontinent before the advent of the British. “This land of unsurpassed fertility has always been a major center of culture and learning” writes Sangeeta Bhatnagar in her book Dastarkhwan-e-Awadh. “It (Awadh) found its zenith under the reign of the Nawabs of Awadh”. Of the nawabs, Awadhi cuisine as we know it today has much to do with the whims, and adventurous palate of its kings.

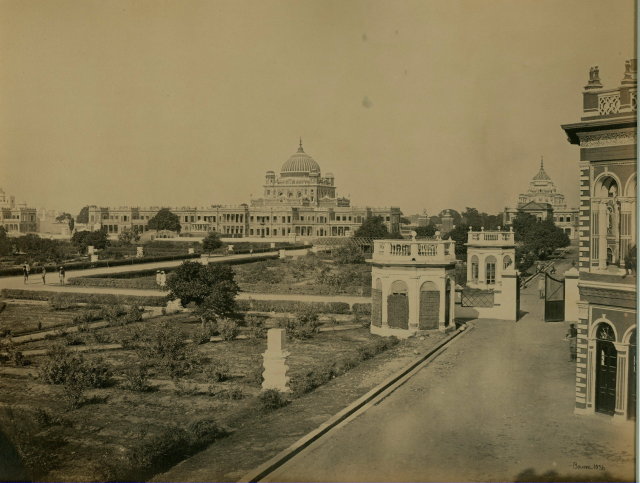

Qaiser Bagh Palace, Lucknow (the residence of Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Awadh) by Samuel Bourne, c. 1866, Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

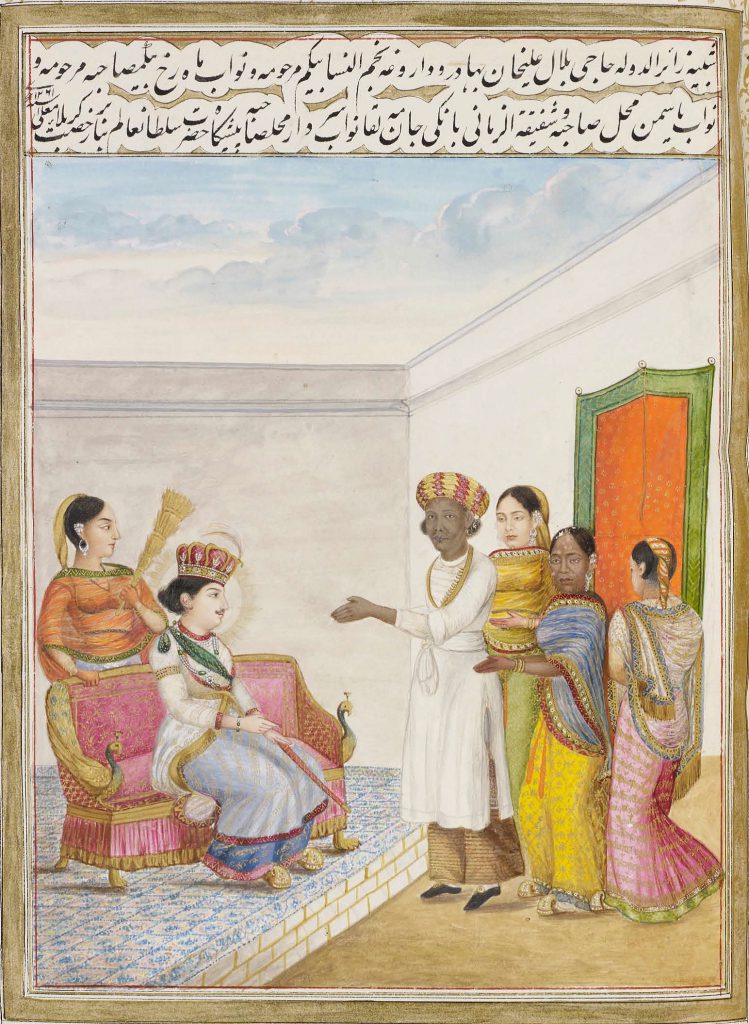

In the later courts of Wajid Ali Shah, specifically, food was more than consumption, it was an experience that engaged all senses, it took and added to the nawab’s love for spectacle and theatre. Ali Shah had in his court khansamas, or courtly cooks unlike any other. The khansamas trained cooks to make dishes so unique, so as to not bore their king and his guests. They melded ingredients from the empire’s lands, and created a repertoire of recipes with local ingredients and others sourced through trade. Under Ali Shah’s supervision, food was taken to extravagant, poetic heights. Kheer was cooled under the white light of the moonbeams, meat was pounded to pastes to make kebabs so soft they defied the need for chewing.

The court of Wajid Ali Shah. Image credit: Royal Collection Trust/Wikimedia Commons

In Dastarkhwan-e-Awadh, Bhatnagar chronicles the variety of the empire’s recipes, such as qaliya, a mutton-dish that is eaten across India today and is representative of the region’s confluences, and its influence of the Shia Kingdom of Persia on the Shia emperors of Awadh. The collection of recipes is evidence of Awadhi tehzeeb or culture, a tradition that lives in the hospitality of those that inherit the fortune of the Nawab’s and Talukdar’s of the region. In India Cookbook, food writer and historian Pushpesh Pant writes about “silver leaf”, a technique where small coins of silver were placed between leather and paper and beaten for hours so they could be transformed to edible foil. “Silver was eaten enthusiastically” he writes. “As it was thought to have aphrodisiac properties.”

Today, it only takes a walk down Lucknow’s lanes to encounter these intricacies – large naans spiked on rods that are eaten with Nihari; old-timer kebab chefs who preside over their tandoors like men on thrones. It is in these conjectures, and more importantly, the lives of its emperors that the cuisine takes form. As Awadhi cuisine remains beloved, we must note the labour of those that commanded the nawab’s kitchens; the farmers and kasais or butchers of the region that induced delicious and novel flavours onto South-Asian palates centuries ago that inform how we eat today.

The presence of Awadhi cuisine marks a time when religious confluence was abundant in the subcontinent. And even as it is incorrectly and inadequately confused with the more Westernised Mughlai foods, the specificities of trade, ingredients and temperament that resulted in the empire’s creations possess a way to understand the history of those that ruled it, built it and cooked within its walls.

Sharanya Deepak is a writer from and currently in New Delhi. Most recently, in 2020, she won the Wasafiri New Writing Prize for the category “Life Writing”. You can read more of her work here: www.sharanyadeepak.com