Blogs

Making of a Museum: The Roots of Education and Outreach

Khushi Bansal

The Education team at MAP is helmed with the responsibility of inspiring and sparking curiosity in children and adults.

According to the internet (although with slight variations), education is defined as “a process of teaching, training and learning, especially in schools, colleges or universities, to improve knowledge and developing skills” (Oxford Dictionary, n.d.). Fundamentally, however, education is so much more than that: it is learning and adapting to the various social, cultural and economic changes; it is about reinventing oneself by improving knowledge systems and broadening horizons. For this reason, museum education is essential as it enables self-reflection and creates a space for kindness and compassion.

The Education and Outreach team at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), our art museum in Bangalore, is helmed with the responsibility of inspiring and sparking curiosity in children and adults alike to create a space for interdisciplinary learning. Art education can be multisensorial as it allows for different kinds of learners to absorb all types of learning with bits of design thinking, visualisation and building perspective. The team is headed by Shilpa Vijayakrishnan, who comes with a background in literature, art and aesthetics. She has worked in MAP for a long time and has seen a remarkable shift as the institution evolved from a place of 4 to 40 people. Shubhasree Purkayasta is a senior education officer, who found herself coming back to the education sector over and over again after having worked in different departments. Kinjal Babaria, an education associate, has a background in the history of art and has worked extensively in the education sector.

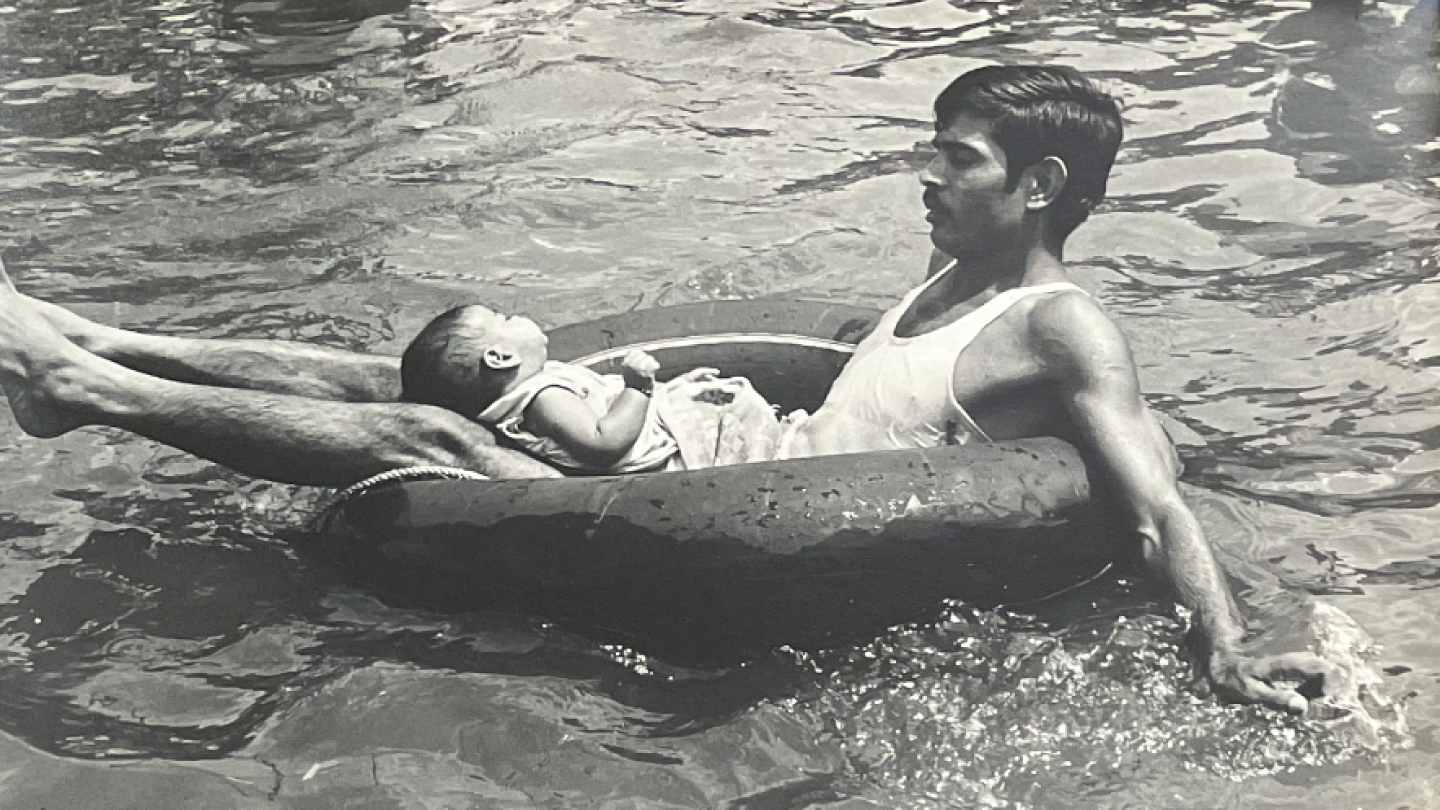

Drifting Toward the Light, Varanasi by Jay Colton, 2002, Silver gelatin print, Image: H. 16 cm, W. 48.2 cm; Support: H. 36 cm, W. 59.2 cm, Varanasi (also Benaras or Kashi), Uttar Pradesh, India, PHY.02313

The department has been around for a long time with the first programme having been realised in 2016. According to Shilpa, “we knew that we wanted it from the start and that hasn’t changed. From the very beginning, there was always certainty around education being very central to what we wanted to do at MAP as one of its core values. We started with school students and over the last five years, we have created and built an audience. Now that we are opening, we actually have an audience that knows of us and that has engaged with us. Schools have come back for several programmes and there are also a few that have come back for every programme. In education, you get to see the impact you are talking about. You are seeing someone engaging in real life, however, it may be.”

Speaking of art education within the current scenario, Shubhasree said, “as I mainly work with school kids I have noticed that in India, art education is not given much importance. We as a department are trying to break that. Kids come from curriculums where art is just this one extra class and it is about drawing and painting. What we do in the workshop is break the idea of art being a skill.” Kinjal continued to add, “in terms of the pandemic, museums were forced to go digital and it is great because now we have a broader audience. Earlier we would only do physical programming that catered specifically to the children in Bangalore. Now that we have programmes online, we have so many schools from different cities that have the exposure to participate in these programmes.” Adding to the points of Kinjal and Shubhasree, Shilpa said, “we have talked a lot about how art can help develop 21st-century life skills like critical thinking and creative thinking. Additionally, using the arts as more than just a technical skill allows you to think about, and reflect on trauma or significant emotional experiences in ways that are fruitful, and therapeutic almost.”

WM. Stirling & Sons, late 19th-early 20th century, Chromolithograph, Image: H. 6.2 cm, W. 8.9 cm; Support: H. 17.9 cm, W. 22 cm, Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom, POP.00501

When it comes to programming the workshops are created keeping in mind two learning patterns. The first is the formal learning programmes that are developed for targetted audiences like educators, people with disabilities and senior citizens. The idea here is to create a programme that is specific to the needs of a community. The secondary layer is more informal where people are invited to take back a new learning by visiting the physical or digital museum space. This helps in taking them one step closer towards enquiry, discovery and learning. Shilpa said, “when it comes to formal learning, we have established pedagogical directions we want our practice to take. All of our pedagogical drives come from constructivist theories which are about learning while doing, and creative enquiry theories. A lot of what we do is very much invested in the idea of dialogue.”

Having a base theory and building upward is always useful as you can control the direction of the workshop. We spoke extensively about the process of ideation and creation, and to this, Shubhasree said, “under the larger programmes, it is a lot of brainstorming and to and fro reviews. Until now, we have had the freedom (before the exhibition) to draw whatever from the collection and curate themes from practically anything. Due to our Indian art collection being so broad and a melange of so many genres and works, it’s fun to look at one theme across times, objects and categories. However, starting in December our approach will drastically change because we have to plug in everything to the ongoing exhibitions. We are working towards that and it is in its very initial phase of ideating as we haven’t developed any concrete workshops yet. Also for workshops, we have developed a loose structure of how to begin and end while keeping the pedagogical ideas in mind. The entire workshop is interactive where we are just facilitators.” Kinjal continued to add, “a lot of times when we decide things, they sound alright on paper but then we are unsure how it will turn out when we are doing it. We are always looking for guinea pigs around the room, and we try out certain ideas and activities with our colleagues. Based on their responses, we get a better idea of whether it works or not.”

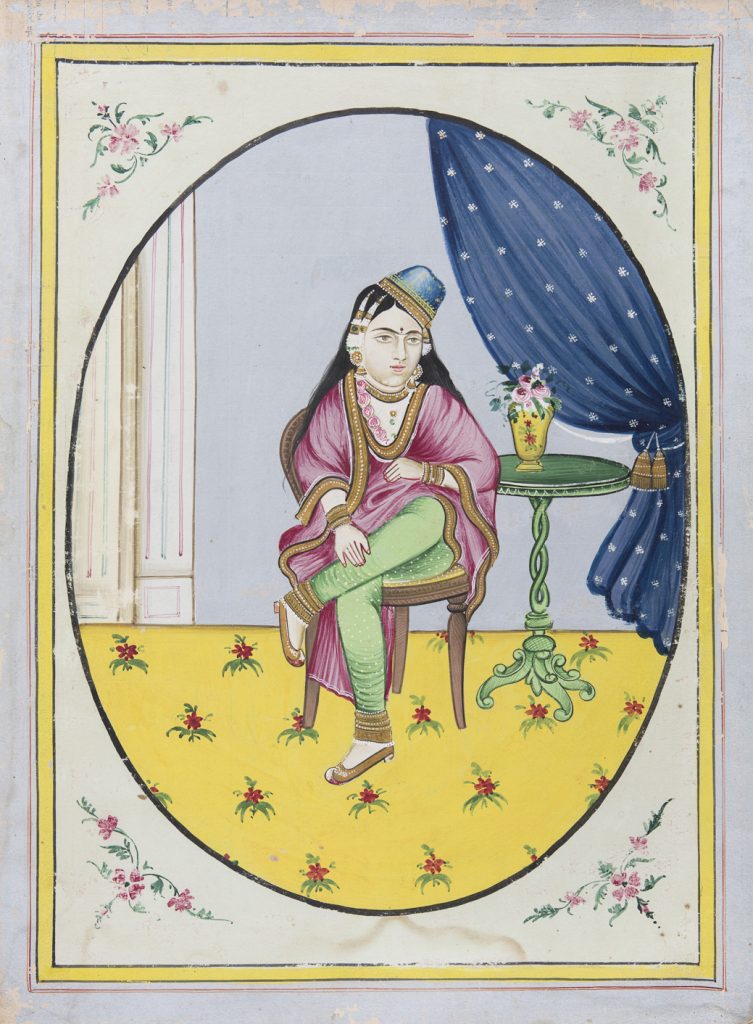

Untitled (Portrait of a Lady Seated on a European Chair), late 19th-early 20th century, Opaque watercolour and gold on paper, H. 40.7 cm, W. 30.2 cm, North India, PTG.01262

A recurring idea in the conversation had been around the space for inquiry where an individual creates their perspective. That being said, it can be rather difficult to create a space which is devoid of judgement and opinion. To this, Kinjal said, “the way we facilitate is not us lecturing and throwing out information. Rather, it’s the way we ask questions to children without directly giving them information. By structuring questions, they can create their own perception of artworks and find their own opinions and stories. The key is to ask the right questions and create a safe space where they feel comfortable expressing themselves; where there are no right and wrong answers.” Shubhasree continued to add, “another important thing that I have noticed is that it’s very important to break that sense of hierarchy between you and the group. Sometimes it’s as simple as your body language: it’s important for participants to feel that we also don’t know everything, like them, and that we are all there to just gain knowledge. You see this hierarchy in the physical space, in the presence of a teacher, as schools have unfortunately continued to build on the structures of hierarchy.”

Shubhasree proceeded to emphasise a recent incident at a workshop, “the workshop was about lines, colours and intuitive drawing. I started with an icebreaker as to what the most important things in an artwork are. I was expecting answers like you draw a line and then you put a colour. Instead, their response to it was ‘draw whatever you want to draw and then colour within the lines.’ Every single child said this; young children are being taught to not go out of the lines.” Adding to this point, Shilpa said, “if you ask anybody to imagine drawing a house, a standard house with slanting roofs, mountain ranges and river is created. I’m pretty sure 99 per cent of people think of this. So, I think breaking out of that mould itself is exciting because you find new ways to approach the works. Also sometimes schools have one-hour periods allocated to art. But one thing that helps (whether it’s kids or adults) is to give people time to open up. You try to be the facilitator rather than the teacher; you are more guiding this conversation than really shoving it in any direction. When it comes to minors, there has to be authority and one of the ways in which you enable a space is to allow the conversation to take any route. You can’t be focused on a point and force it and not shut those down as it is contradictory to what you are working towards. Since you are saying the whole point of engaging with art is to open conversation, those conversations are not dictated by what you want but rather by where the people want to take it.”

Although contradictory to my previous question, a favourite of this series has been about favourite artworks in the large MAP collection. Shilpa started by saying, “I don’t have a favourite artwork that comes to mind. I can say that one of the earliest things that brought me here was my interest in popular culture which still remains. There are a lot of things that I find fascinating and I think in general I am attracted to the weird ones. Those where you think what is happening? What was this person thinking?”

Rasraj Ras Manjari by Madhav Chandra Das, early 21st century, Woodcut print, Image: H. 27.5 cm, W. 39.4 cm; Support: H. 35 cm, W. 49 cm, Battala, Calcutta (now Kolkata), West Bengal, India, POP.01720

Boy with Torch by Ganesh Pyne, 1970, Tempera on paper, Image: H. 50 cm, W. 45 cm; Frame: H. 68 cm, W. 64 cm, India, MAC.00689

Shubhasree continued to say, “I like the quirky stuff that you don’t expect to see in a particular medium. There is a miniature showing a homosexual couple cuddling – it’s so cute and not what you expect. I like it because you don’t see such themes in miniatures. I also like quirky stuff like textile labels and Battala prints, there is so much to uncover!” Finally, Kinjal concluded by saying, “I am still exploring the collection as I have seen and engaged with a very limited selection. However, recently, I worked on Ganesh Pyne’s Indian modern art, and I find his work fascinating.”

A recent graduate from Central Saint Martins, London, Khushi Bansal is an aspiring curator with a keen interest in baking a perfect loaf of bread. She is an Archivist in MAP’s Collection team.

References

1. Oxford Dictionary. n.d. “education noun – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com.” Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/education.