Essays

How to Sniff Out a Fake? Long-Distance Trade and the Madras Handkerchief

Adhitya Dhanapal

This essay explores the history of a particular kind of handloom cloth from Madras, commonly referred to by its trade names, the Telia rumal or the Madras Handkerchief.

The very mention of double ikat evokes images of intricately woven elephants, conch shells and floral motifs: Patan Patola or Sambalpuri ikat sarees were prized commodities amongst collectors of luxury goods within the Indian subcontinent and as far as Zanzibar and Indonesia. However, if we were to look at sheer volume of exports, insatiable consumer demand and total number of weavers employed in its manufacture, the checked and striped textiles produced in the Coromandel Coast were by far one of the most important centres for ikat manufacture and exports. The coastal belt of today’s Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu has historically been an important powerhouse for the manufacture of a broad range of handloom cloth, made entirely using vegetable and mineral dyes that attracted traders from across the world. Though there are many literary references in Sanskrit and Tamil sources, the earliest port entrepot is the Roman settlement of Arikamedu (located in Puducheri) dating from the 1st Century BCE.

This essay explores the history of a particular kind of handloom cloth from Madras, commonly referred to by its trade names, the Telia rumal or the Madras Handkerchief. Though visually different in their design, what unites these two kinds of fabrics is that they are produced within the same region and employ similar techniques of natural dyeing. The first section will explore the traditional artisanal process of manufacturing this cloth, its salient design features and the ways in which it underpinned world trade in the period before the advent of industrialisation. The second section picks up in the late 19th century and demonstrates the resilience of the Madras handkerchief to the forces of industrialisation and colonialism and explores how the textile continued to thrive right up to the 1960s.

I

A replica of an Ikat weavers’ workshop, Dakshinchitra. Notice the triangular frame where skeins of dyed yarn are knotted together before preparing the warp. Courtesy: Dakshinchitra Museum, photograph by Sam van Strien

The semi-tropical climate of the Coromandel is ideal for the cultivation of cotton and moreover, the proximity to the Bay of Bengal ensured high humidity which is highly conducive for weaving. What gave the weavers from this region an edge over others was their superior dyeing techniques. Besides using a wide range of naturally occurring vegetable and mineral pigments, the weavers of southern India also mastered the art of mordanting. A mordant is an inorganic oxide that assists the dye in fixing to the cloth. Thus, the cloth manufactured were guaranteed with “fast colours”, i.e. unlike other dyed textiles that tended to lose colour with age and every wash, the textiles from the Coromandel retained their lustre with use and time. The technique of getting the desired colour is as follows: after the monsoon, the locally spun yarn is first boiled in water and ash. The starched yarn is then soaked in sesame oil and later, the yarns are also soaked in a solution of sheep or cow dung in order to bleach the cotton yarn.

The yarns are then washed again and soaked in the mordanting solution (usually consisting of alum dissolved in water) before they are soaked in the dyeing vats. The exact recipes for these natural dyes emerged from a period of endless experimentation and tend to rely on local conditions such as the alkalinity/salinity of water or the quality of local dyeing ingredients.

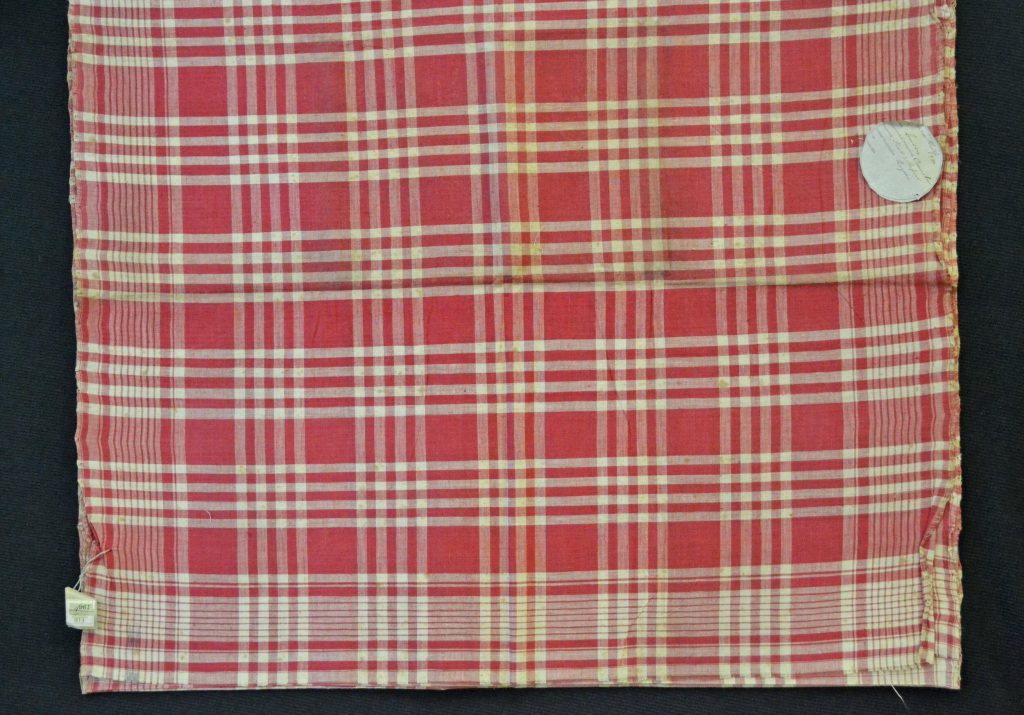

Telia Rumal (fragment), late 19th century (made), cotton ikat, 208 x 111 cm, Courtesy: V&A Museum, London

Located at the very heart of the Indian Ocean trade routes that stretched across east Africa, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, the port cities on the Coromandel such as Masulipatam, Chirala, Pulicat amongst others became important sites of trade and commerce. Besides a reliable local supply of cotton and raw materials, the labour force consisting of spinners, warpers, dyers and weavers were constantly willing to adapt, learn new techniques and were willing to have flexible production processes in order to tap into new markets. One such instance of the deftness with which south Indian weavers quickly came to dominate the market is the Telia Rumal using the double ikat technique.1 The Telia Rumal would ideally be a running cloth around one yard width and would be woven as a series of squares in red, black and white. As seen in the photo below, the final product resembled a square piece of cloth with a square border that encased a grid-like design profuse with geometrical patterns.

The square or kattam lies at the heart of every design with endless scope for experimentation. The dyeing process would imbue the cloth a glimmering oily finish with a distinctive smell of the sesame mixed up with the myrobalan fruit.2 This smell is how the humble square cloth, popular amongst the fisherman community as a loin cloth, came to be called the ‘telia’ rumal (tel meaning oil).

Fisherman wearing a Telia Rumal Lungi in the Andhra coast, circa early 20th century. Image source: http://www.asiantextilestudies.com/telia.html

The coming of the Portuguese marked a distinct shift in the nature, scale and ultimately design of the handloom trade in the Coromandel. With the expansion of long-distance trade in the 16th century, this symbolically rich and ornate pattern would give way to a simplified checks and stripe pattern suitable to export markets.

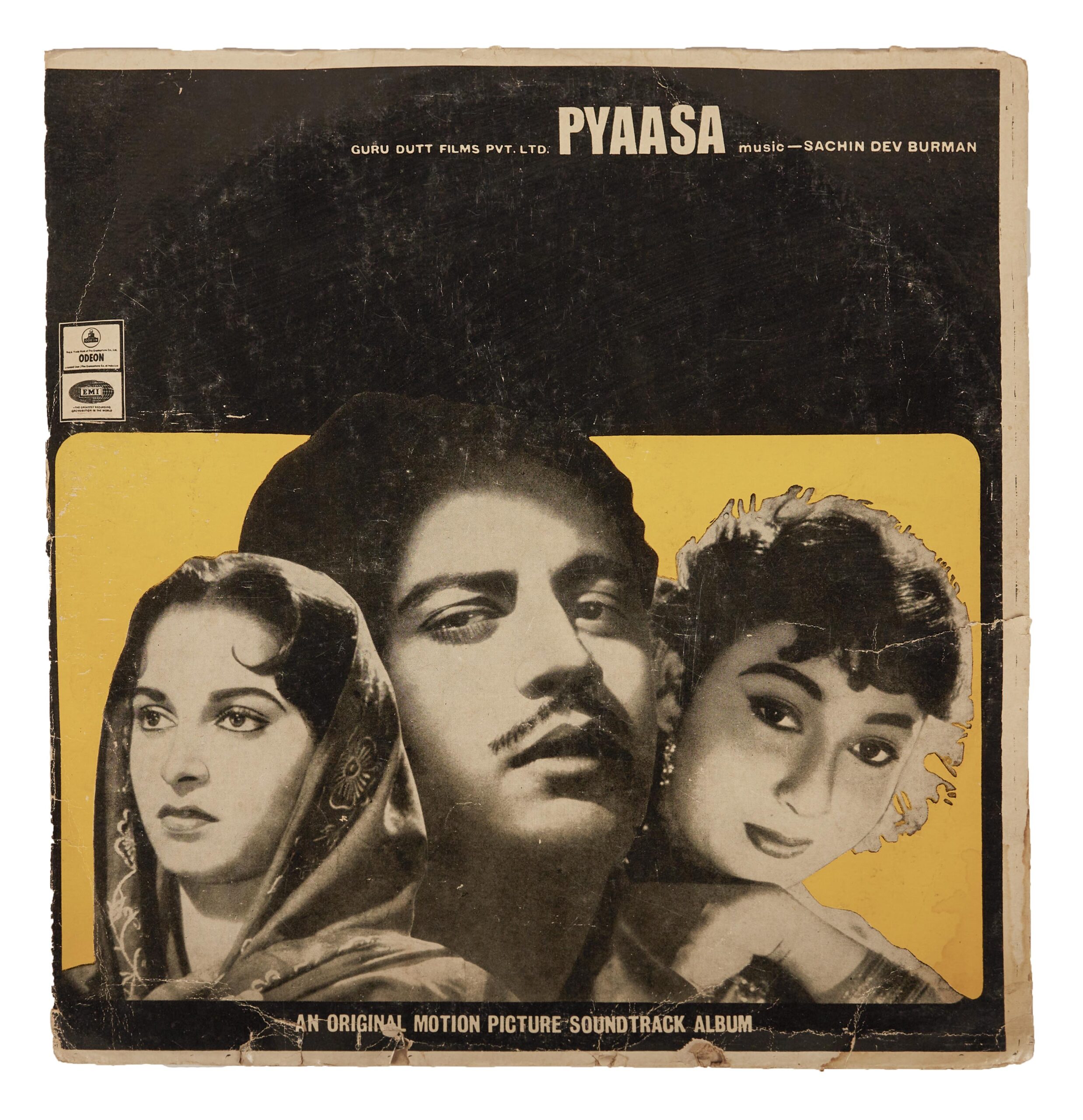

Madras Handkerchiefs, c. 1855 (made), Tamil Nadu, woven cotton, 770 x 92.5 cm, Courtesy: V&A Museum, London

The Portuguese, having found an alternative route to India around Africa, would soon use their strong navy to crush local trade networks and integrate the Indian Ocean trade with the Atlantic slave trade. The opening up of the Americas to European settlers created a frenzy for acquiring slaves from West Africa who could be shipped into the sugar and tobacco plantations of the Caribbean and Brazil. With increasing demand for slaves, the African coastal chiefs who captured and sold off up-river communities as slaves started commanding an increased position within the Atlantic triangular trade. Not satisfied with gold or guns alone, these African consumers began demanding bales of bright coloured textiles. We need to recognise that around 300 years ago, clothes were one of the most important symbols of prestige and status. Chiefs and Kings across the world vied for a diverse wardrobe to demonstrate their power within courtly settings. The colourful cotton cloths from India were thus tremendously valued within these contexts, they were sometimes even attributed with magical properties of healing!

Thus, scholars have argued how the demand and desire for cotton is what connected the markets of the Indian and the Atlantic Ocean worlds. In a highly diverse world with different notions of value and money, an increasing desire and consumption of cotton textiles not only integrated the littoral economies of east Africa, the slave coast, the Coromandel coast and Java with one another but also with their own respective hinterlands. The artisans were able to churn out handloom textiles in a myriad of colours and patterns with a tremendous amount of flexibility.

Madras Handkerchiefs, c. 1855 (made), Tamil Nadu, Woven cotton, 576 x 75.5 cm, Courtesy: V&A Museum, London

II

The historian Prasannan Parthasarthy has sketched out a detailed picture of how production, credit and trade in handloom dyed textiles underpinned the formation of colonial states in the early 19th century. He also argues that the competition from the Indian Ocean textile trade was a major impetus for the adoption of labour-saving technologies in the West. The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain and colonial expansion of the East India Company are thus deeply intertwined. The story of how colonialism and industrialisation devastated the livelihoods of the Indian handloom cotton textile industry is well-documented. However, unlike other equally renowned fabrics from South Asia such as the Dhaka muslins, the intrinsic value of the Madras Handkerchiefs were able to resist attempts at mechanical reproduction as well as the usage of chemical alizarin dyes. In general, the handloom industry in the Coromandel continued to be resilient and negotiate the various hardships of colonial rule and rapid industrialisation. The handloom producers of southern India took advantage of the elaborate material, legal and financial infrastructure that the British Empire set up to facilitate long distance trade.

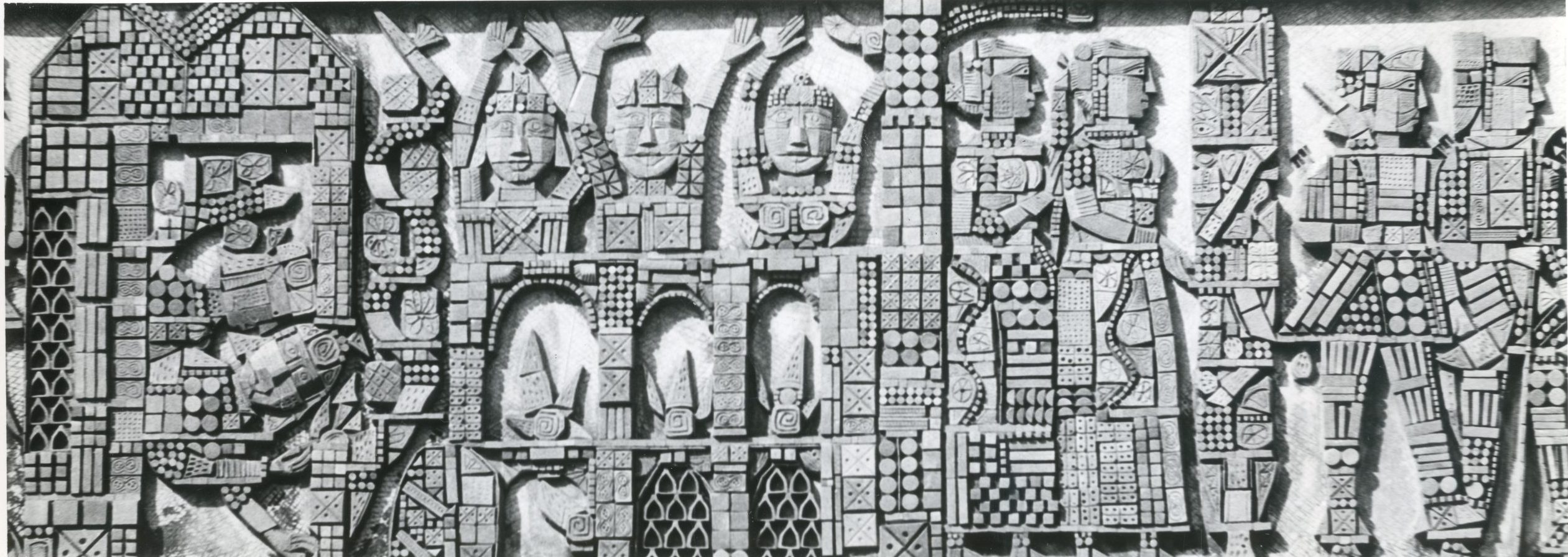

A modern rendition of the Kalabari traditional gear that still evokes the checks of the Madras Handkerchief, Image credit: Sigrid Barten, Kreuz und Quer der Farben: Karo- und Streifenstoffe der Schweiz für Afrika, Indonesien und die Türkei (Museum Bellerive Zürich, Modemuseum im Münchener Stadtmuseum, Museum des Landes Glarus Näfels; 1997)

The high volume of trade resulted in a standardised pattern of a long running cloth of 1 yard width and 24 yards in length. Each yard was marked with a white stripe to make the square handkerchief. The cloths were usually dyed in reds, blues, blacks, browns, yellows, greens and black. These fabrics were deemed highly desirable in western Africa or what is now Nigeria and Sierra Leone. The 24-yard cloth was cut in three parts of 8 yards each out of which 4 yards were used as the lower cloth, 2 yards as the upper cloth, 1 yard as a headcloth and 1 yard as a handkerchief. As Madras was the largest port of export, this fabric came to be marketed as the ‘Madras’ handkerchief. The Madras Handkerchief came to become an integral cloth in the life cycle rituals and cultural identity of the Kalabari tribe in the Niger delta region.

The two firms that specialised in the export of the handkerchiefs were the Switzerland-based A Brunnschweiler and Co. and the British firm, Coles and Co. A Brunnschweiler and Co mastered the art of alizarin dyes—these new chemical dyes were the direct result of the new burst of chemical technological innovations that emerged in the late 19th century in the German Empire. Significantly cheaper to manufacture, these dyes had disrupted the old centrality of vegetable and mineral dyes that the Indian artisans had mastered over the course of many centuries. The Swiss firms, who had a good understanding of the West African markets, started coming up with a new line of machine-made Madras Handkerchiefs that exclusively used chemical dyes that were made in Swiss and British factories. These cheap substitutes started flooding the West African market and threatened to push out of the Coromandel producers. Despite the cheaper price and identical design of the Swiss substitutes, the African consumers continued to prefer the “real” Madras Handkerchief. The reason: discerning consumers would first sniff the cloth and recognise the special smell of sesame oil and vegetable dyes! This resulted in the fabric being marketed as the Real Madras Handkerchief!

An imitation telia rumal probably made in England in the early 20th century, Printed cotton, 168.4 x 94 cm., Courtesy: V&A Museum, London

Histories of textiles have tended to emphasise the design and visual appeal of the fabric. Instead, a focus on the social histories of textiles opens new horizons of interest such as technologies of production, networks of long-distance trade and the centrality of consumers’ taste in shaping our collective futures.

Adhitya Dhanapal is a PhD candidate in History at Princeton University. His research looks at the political economy of handloom co-operatives in Southern India. Before this, he studied at the School of Arts and Aesthetics and Centre for Historical Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

References

1. Ikat, coming from Malay/Indonesia origins, refers to a technique of tie-dyeing the yarn before weaving by using threads to block out certain parts of the yarn. Carefully dyed in this way, the warp and weft tend to be multicoloured and produce an intricate pattern when woven together. The Southeast Asian etymological origin does not suggest that this technique originated from the Indonesian archipelago since the technique is prevalent across Central, South and Southeast Asia.

2. Locally called karakkaya or harad, the myrobalan fruit is crucial for the rich, earthy, red coloured dye that is prolifically used in Telia Rumals.